It does not matter that my youngest son is now on the same university campus where I am a professor, or that his dormitory is one mile from our home. Saturday before last, after Laura and I moved him in with his best friend, I went home, sat on his bed in his now empty bedroom, and wept.

The house is much quieter. Even Otis the dog seems melancholy.

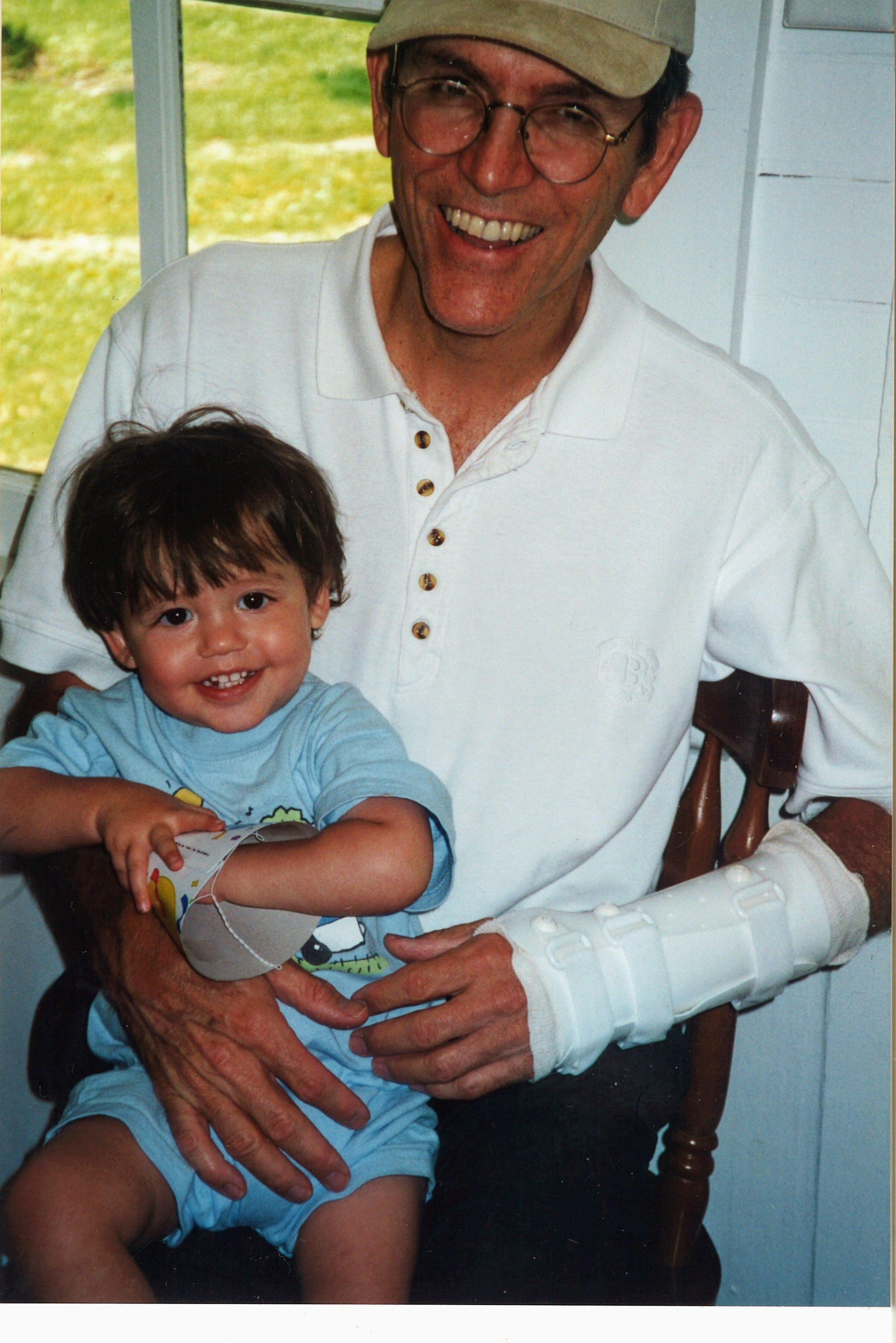

Granddaddy and Ben

It’s a miracle that the boy is still alive, really. All three of our boys—Chandler, David, and Ben—were particularly hard on their bodies and hard on each other. At last count we did something like 18 or 19 emergency room visits. We knew we were going too often when one of the attending ER doc’s came in one particular Friday night. We had brought David in to get stitched up. Recognition flashed across the doctor’s face, and she flashed a hospitable smile: “Oh hi! How are Chandler and Ben?”

Ben, the youngest and this most recent college student, was responsible for the majority of the ER visits. He even prompted a visit to the most remote emergency room on the face of planet Earth. We were with students in Easter Island, somewhere out in the south Pacific, on a study abroad trip. Ben ripped his knee open while running down a hill from visiting some of the Moa or some such ancient artifact.

We made our way to the hospital. Once Ben was finally admitted, I got myself thrown out of the ER. I wanted to take a picture of Ben in the most remote emergency room on the face of the planet. I know the value of a good story, and the value of a good picture. The doctor found this annoying. He caught me taking the picture, and shouted at me. He didn’t even let me get to Ben’s room, told me to go wait in the waiting room. I did not like him. The doctors at Vanderbilt are always much nicer to us.

But this young good-looking doctor did seem to like my good-looking wife. He apparently talked to her at great length. He told her to clean Ben’s wound. “Everyone does everything here,” he said in his sort of condescending way toward those who don’t live somewhere like the most remote inhabited island on the face of planet Earth. So Laura cleaned the wound. He grumbled some more in his dashing way, and finally stitched Ben up. We still made it in time to see the evening entertainment of the scantily clad island dancers do their traditional dances. Thank the Lord for that.

Anyway, after one earlier ER visit in Nashville, I told the boys that they had to slow down the damage they were doing to their bodies. I explained that we simply could not afford to keep paying the ER deductible. Their getting-stitched-up habits were costing us too much.

A few weeks later, I noticed that Ben’s temper was getting the best of him. This ten-year-old had the biggest heart in the world, a tender, kind boy who also happened to be one of the best and dearest conversationalists among all 21st century adolescents. But his temper was starting to get to him. I could understand it. His brothers would taunt him to no end.

So one night I put him to bed. Oh the sweet years of lying in bed beside one’s child, after having read them a book, and then to talk when the lights are out, his head on my shoulder, both of us staring up at the ceiling, talking about the day, about life as a ten year old sees it. It is one of the finest of human pleasures.

I moved to parental direction: “Ben, your temper is going to cause you some problems. You need to take care. ‘Slow to speak, quick to listen, slow to anger.’ Your anger is going to get you in trouble.” “Ok, ok,” he said, impatiently.

Less than twenty four hours later I went upstairs to his brother’s room. We had had company for dinner that night. All our boys and the sons of our friends were all congregated in the bedroom. Ben’s older brother was standing at the foot of his bed. Ben was standing on the bed. The older brother was taunting. I saw Ben clench his fist. Fire rolled over his countenance.

“Ben,” I said firmly. No response. He just stared at his brother. “Ben,” I said more firmly. Still he paid me no heed. Then he moved from a slight crouch toward a pounce, his fist now overhead, lunging off the end of the bed in an effort to pummel his brother. “Ben!” I shouted. His brother simply stepped out of the way. Ben, now high in the air, could not divert his trajectory. And at the end of his trajectory, on the floor, was a Galileo thermometer, a 14” tall glass cylinder which comes to a slightly dull point of glass at its top, perfect for piercing the human body when it’s hit just right. Ben’s foot hit it just right.

The glass cylinder split open as Ben’s full weight came down on it. It fileted his foot. After the Vanderbilt ER doc’s would call in all the other ER attending physicians and residents to stare at the boy’s heel split open to all the world, and after they did their magic, his heel would look like a baseball, stitched up all the way from one side of the to the other, a perfect semi-circle stitched into his heel.

But I get ahead of myself. Ben came down on the Galileo thermometer, and instantly rolled into a ten-year-old ball of heaving pain, the bleeding instantly profuse. I grabbed a full sized bath towel, wrapped up his foot, and began shouting for Laura. “We’ve got to go, got to go, got to go,” I said like a drill sergeant shouting down the steps. Laura jumped into the driver’s seat, I held Ben in the backseat, and off we were for another trip to Vanderbilt Pediatric ER.

Ben was, as he always is in moments that require it, courageous and quiet. By the time we reached the corner of 12th Avenue South and Wedgewood, he had bled through the bath towel. That was when the sobbing started. I tried to comfort him: “It’s okay, buddy, it’s going to be okay.”

“I’m sorry, Dad, I’m sorry,” he sobbed.

“It’s okay, it’s okay,” I said. But I was thinking that I hoped he would remember my moral lesson about his temper next time he was tempted to pummel someone.

But I was oblivious to his concern. “I’m sorry, Dad, I’m sorry,” he went on. “I’ll pay the deductible,” he wept.

Only out of the mouths of babes comes such innocence.

And so Saturday after last, I sat on that bed on which Ben had stood to pummel his brother, in the room that had become his room after his brother made his own way to the west coast years ago at the start of his university days. And I grieved the passing of one season of life: the loss of its tenderness, its laughter, its joys.

But I shall not miss the exhaustion of parenting, the exasperation of raising boys, the daily reminders of how little control we parents have in a world that constantly tells us all the dangers we must somehow avert.

But oh how I shall miss this boy and his brothers living in our house, their daily joys and struggles our own. And yet, of course, my tears are tempered by my joy as I watch them make their way in the world, praying for God’s mercies, that they shall be men fully alive, and thus the glory of God.

Join us on our podcast: