Why are there different narratives around race in the United States?

Some believe that the US is a “shining city on a hill” which stands as a beacon of truth and justice in the world. But those paying attention to the country’s inner conflicts - most notably its violent, graphic history of deep-seated racism - sense some major contradictions in such a narrative. To use the famous words of James Baldwin, such idealism is “The Lie” that the country has been trying to preserve since its inception.

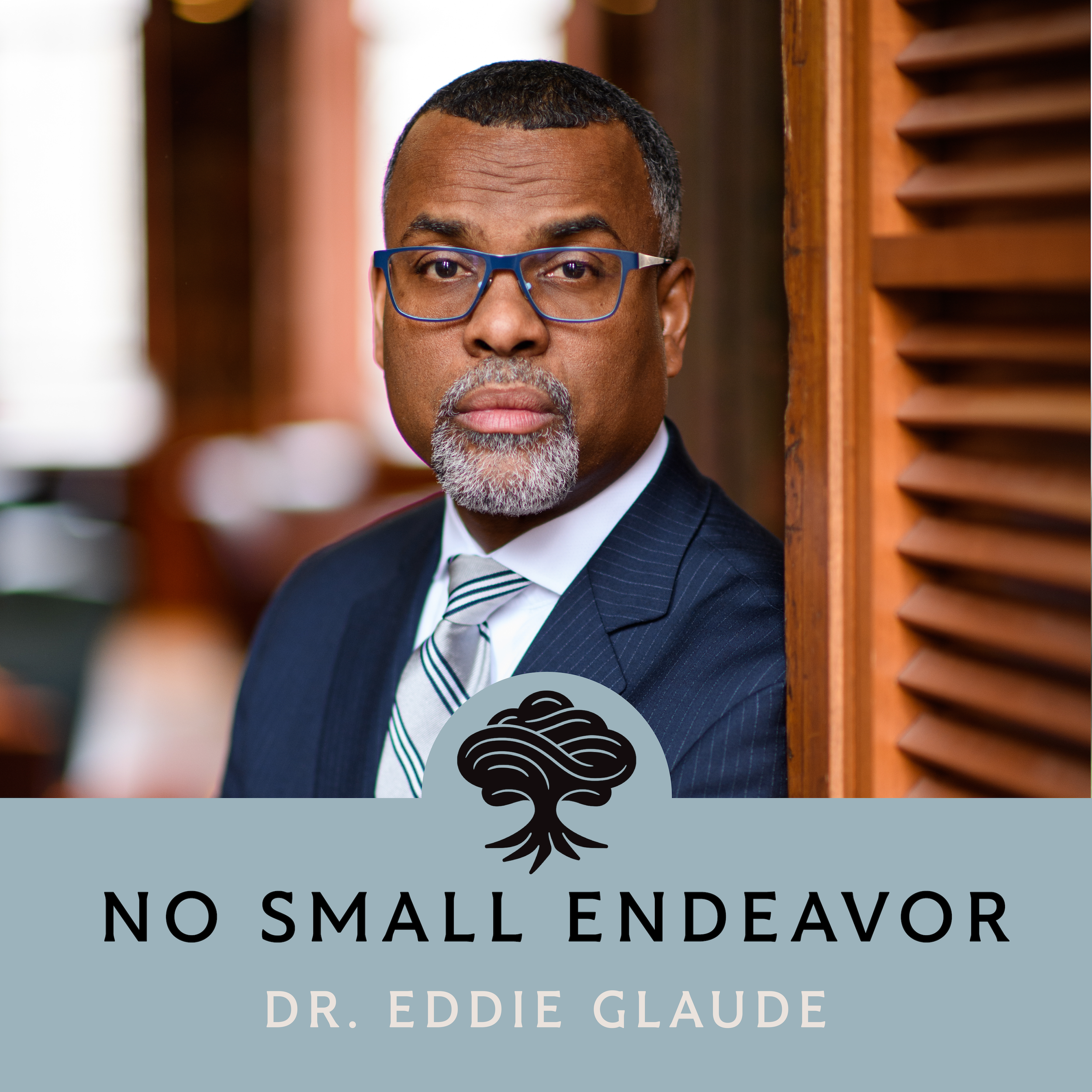

In this episode, Dr. Eddie Glaude discusses his book Begin Again: James Baldwin's America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own, which calls for a reckoning for the people and institutions responsible for perpetuating “The Lie,” and offers hopeful counter-truth that he believes can help us reform and reset after the wrongs that have been done.

Show Notes:

Similar episodes

Resources mentioned this episode

JOIN NSE+ Today! Our subscriber only community with bonus episodes, ad-free listening, and discounts on live shows

Subscribe to episodes: Apple | Spotify | Amazon | Google | YouTube

Follow Us: Instagram | Twitter | Facebook | YouTube

Follow Lee: Instagram | Twitter

Join our Email List: nosmallendeavor.com

See Privacy Policy: Privacy Policy

Amazon Affiliate Disclosure: Tokens Media, LLC is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

Transcript:

Lee: [00:00:00] This is No Small Endeavor. I'm Lee C. Camp. You're listening to one of our "best of" episodes with Princeton professor Eddie Glaude, on his recent book on James Baldwin. I'm particularly fond of this interview. Enjoy.

I'm Lee C. Camp and this is No Small Endeavor, exploring what it means to live a good life.

Today, Dr. Eddie Glaude, professor at Princeton and author of the New York Times bestseller Begin Again: James Baldwin's America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own.

Eddie: The kinds of histories we tell matter, because what you choose to leave out oftentimes reveals the limits of your idea of justice.

Lee: Today, a penetrating conversation around the racism that many call America's original sin, and the calls to what it might mean to untangle [00:01:00] and dismantle it.

Eddie: If God doesn't make us more loving, if God doesn't make us more expansive, then it's time we got rid of Him. And of course, a lot of people raise their eyebrows at that one.

Lee: All this, coming right up.

I am Lee C. Camp. This is No Small Endeavor, exploring what it means to live a good life.

As a boy, I was enthralled with science and technology. To care about history made no sense to me. It would be in my early twenties though, that I began to understand that I could never understand myself, my community, my sense of purpose, apart from an understanding of the history of how I, or my community, or my sense of what matters ever came to be.

Without grappling with our history - its good, its bad, its ugly - we simply cannot see [00:02:00] and cannot move forward. That's one way of framing this poignant and pressing conversation we share today with Professor Eddie Glaude.

One of the nation's most prominent scholars, Dr. Eddie Glaude Jr. is a passionate educator, author, political commentator, and public intellectual.

Raised in Moss Point, Mississippi. He's earned degrees at Morehouse, Temple, and Princeton, including his PhD in religion at Princeton. He served as the president of the American Academy of Religion and is James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor of African American Studies at Princeton University.

We began today discussing his recent New York Times bestseller, Begin Again: James Baldwin's America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own.

Welcome to Nashville, Professor Glaude.

Eddie: Oh, it's a pleasure to be with you.

Lee: Yeah.

Eddie: Looking forward to the conversation.

Lee: Pleasure to have you with us.

I would like, if, if we may, to define kind of very quickly, two or three sentences with each definition, some major constructs that's used for the book, and then maybe we can [00:03:00] weave back in and talk about how that relates to the work of James Baldwin.

'The Lie,' I guess, is one of the first that stands out so much. So what, what is 'The Lie?'

Eddie: Yeah. 'The Lie' is this, the kind of-- the stories we tell ourselves to absolve us, ourselves of our sins in some ways. When it comes to the issue of race, it's this kind of broad architecture that allows us to imagine ourselves as the redeemer nation, as the shining city on the hill, when in fact there are these practices that contradict that self-imagining, particularly when it comes to race.

So we imagine ourselves as an example of democracy achieved, when in fact the very notions of freedom that animate the American project are predicated upon intimate understandings of unfreedom. And then we build out a host of meanings around the folks who bear the brunt, the burden of those lies. So it's not us, the story goes, it's them.

They lack mental capacity. They aren't quite human. They're [00:04:00] lazy. They're driven by the passions. So they're a host of lies we tell about folk who bear the burden of our desire for free labor, our desire for the exploitation of other human beings in some ways. And so it's this broad architecture, this discursive framework that allows for a certain understanding of who we are as Americans, as white Americans, and a certain kind of framing of, of those who are not.

Lee: So then the, the 'values gap' is another one that relates, obviously, to 'The Lie.' So tell us, kind of describe that for us.

Eddie: So 'The Lie' is what we tell to justify the valuation that is at the heart of, of the project. So, you know, Baldwin wrote an essay, uh, in 1964, titled "The White Problem," and he said, "The men and women who founded this country knew [00:05:00] that the men and women that they had, held as slaves were in fact human beings, but they had to deny that they were human beings, 'cause if they weren't, then no crime would've been committed."

And so the value gap is this view, it's not a belief, because it could obtain without you have, holding those beliefs, is this view that some people, because of the color of their skin, ought to be valued more than others.

The idea that God is no respecter of persons and acts doesn't obtain, because we've organized a world in which certain bodies are valued, other bodies are devalued, and then advantage and disadvantage is distributed along the lines of that differential valuation. And it, it, it results in a world, in a society more specifically, where generalized disregard is justified.

I introduced the value gap for a reason - because it's at the [00:06:00] heart of the, the achievement gap. It's at the heart of the wealth gap. It's at the heart of the empathy gap, right? There's something about the way in which certain human beings are viewed and other human beings are not, and I think understanding that helps us grab hold of the contradictions that are at the heart of the country.

Lee: Third piece, the betrayal.

Eddie: Yeah.

Lee: Which, uh, certainly as we talk more about Baldwin we'll encounter a great deal, but kind of give us a abstract definition of that.

Eddie: There are these moments when ostensibly-- what is the greatest experiment in trusting human beings to govern themselves, which is the American project.

There are these moments where we repeatedly turn our backs on the ideals that define this constitutional republic. And so the betrayal is a specific iteration of that, [00:07:00] where we're on the cusp of imagining ourselves differently, on the verge of a genuinely multiracial democracy, and we double down on the value gap.

So you can imagine at the moment of the Revolution, and you get the language of the Declaration of Independence. You get this language that all men are created equal, and then you, you see the elements of democracy being articulated by the founding fathers, and then immediately that we have to reconcile those principles with the institution of slavery, right?

'Cause you see, at the moment in which we give voice to the principles of the Declaration and the Constitution and the like, or what would become the Preamble of the Constitution and the like. We see Black people in Massachusetts petitioning the [00:08:00] Massachusetts State Assembly, right, using the same language. It's not applicable to you.

And we can offer a number of different examples of moments where the nation gives voice to these extraordinary principles and then refuses to live them, because of a commitment to the value gap and the lies that sustain it.

Lee: So let's go back a little bit to, to, to 'The Lie' and explore that a bit more with your work on Baldwin.

And for Baldwin, it seems that you're, you're pointing us toward this notion that doing history, the work of history, the practice of the discipline of history, and/or for him, a writer, is kind of envisioned as this moral practice, and a moral practice specifically understood under the notion of bearing witness.

Eddie: Mm-hmm.

Lee: [00:09:00] So would you kind of describe that more for us?

Eddie: Absolutely. I mean, it's a moral practice in the sense that the stories we tell have everything to do with the kinds of human beings we take ourselves to be. Stories are really critical - and this is Aristotle - to character formation.

And so the way-- the kinds of histories we tell matter, because what you choose to leave out oftentimes reveals the limits of your idea of justice.

Lee: Ooh. Would you take that last sentence again?

Eddie: You see, what you choose to leave out often reveals the limits of your idea or conception of justice.

Lee: Mm-hmm.

Eddie: Who you choose to leave out...

Lee: Right. Yeah.

Eddie: ...often reveals the limits of your conception of justice.

So what Baldwin is insistent upon is that we tell ourselves these stories, right, in order to perpetuate or protect our innocence, when history is replete with our sins, as it were. And if we're going to be otherwise, we're gonna have to [00:10:00] confront those sins, right?

And so history is that battleground. And in this sense, you know, it's like, um, Frantz Fanon and The Wretched of the Earth, a Martinican, uh, writer in the 1960s, said that, you know, the colonizer is not content with simply colonizing.

Lee: Right.

Eddie: Taking over the land, government-- they must go back into the history of the colonized and wipe it clean, to say that there was nothing worth doing it. Or Hegel would say, "Africa has no history," you know?

And those become part of the justificatory language, right. That's the justificatory move. Right? Part of 'The Lie,' as it were.

So history is critical, and particularly in, in a death-dodging civilization like our own, right? We're always prospective, we're always future-oriented. So the past is forever left behind. And, and Baldwin is like, no, no, no, no, no, no, no.

Lee: So, so this obviously relates to the common refrain, uh, where some will object, "just let the past be the [00:11:00] past."

But you're pointing to a very different way of understanding the past.

Eddie: Oh, absolutely. What Faulkner's Requiem For A Nun, right? "The past is not dead. The past is not even past." Right?

Lee: Yes.

Eddie: Uh, or that, that line that Mark Twain-- that is attributed to Twain, you know, "History doesn't repeat, but it damn sure rhymes." You know?

[Lee laughs]

Uh, and so, exactly. I think this insistence on, you know, understanding that our present, our present is in so many ways, right, in need of a past to account for it.

The moment we're in is always calling for an account of itself, and our evasion has everything to do, at least to me, with avoiding the mirror. Confronting the shards that lay beneath our [00:12:00] feet.

Lee: I don't know if you, this is a quote from you or you quoting someone else, but in, in one of your speeches, I, I reviewed, um, "The ghosts of the past have us all by the throat."

Eddie: Oh, that's me.

Lee: Yeah. [Laughs]

Eddie: Yeah, that's me.

Yeah, you know, I, I, I was just thinking about this in relation to the pandemic. I was writing about this.

Over a million people are dead. And I'm a southern boy. I'm a deep southern boy. I'm from Mississippi, the Gulf Coast. And, you know, back home when pe-- people would say, "when folk don't die right, they don't stay in the ground."

Lee: Hmm, hmm.

Eddie: And so our ghosts haunt. They're everywhere. And you know, it's like the character in, in The Jolly Corner in Henry James, right?

You know, you, you see the ghost, you deny the ghost as revelatory of who you are, and then you deny it and then you go ahead and behave like a monster. "We're not them!"

And, and in-- and even in the midst of the denial, you end up being monstrous, you know? [00:13:00]So yeah, that's me, the ghost haunt. Yeah.

Lee: You are listening to No Small Endeavor and a conversation with Professor Eddie Glaude.

I love hearing from you. Tell us what you're reading, who you're paying attention to, or send us feedback about today's episode. You can reach me at lee@nosmallendeavor.com.

You can get show notes for this episode in your podcast app or wherever you listen. These notes include links to resources mentioned in the episode, as well as a PDF of my complete interview notes, as well as a full transcript.

We'd be delighted if you'd tell your friends about No Small Endeavor and invite them to join us on the podcast. Those sorts of conversations go a long way toward extending the beauty, truth, and goodness we're seeking to sow in the world.

Coming up, Eddie and I discuss the troubling ways in which American history has been told [00:14:00] and what it might mean to start untangling the history of racism.

You close the-- I, I guess near the, near the end of the book, you tell about your relatively recent journey to Montgomery.

Eddie: Yeah.

Lee: And that, that resonated with me because I actually just got off a trip two weeks ago with some students for my first time to see the Legacy Museum.

Eddie: Yeah.

Lee: EJI's Legacy Museum and the, um, memorial to, uh, lynching. But, it seems to me that it's a very powerful way of trying to do history that's trying to grapple with, with these ghosts.

But talk a little bit about your experience of that and how you see either EJI or others who are trying to do history telling in a way that grapples with the realities in the way that you would hope that they would.

Eddie: Yeah. I think the, you know, the way in which Americans like to tell their, their stories is, is all this, these triumphant, progressive narratives, [00:15:00] right?

We're always already on the road to the more perfect union. And it's the most efficient kind of... it's an ideological confessional, right? We're always on the road to the more perfect union, so we confess our sins and be absolved of them because we're always on the road to a more perfect union, as it were.

What I love about what EJI has done, what disturbed me, in a good sense, it, it unsettled me, is that it refuses the progressive narrative. So typically civil rights tourism is all about, look how bad it was and look how, look at the courage of folk in overcoming it. So there is this kind of narrative arc.

And the Legacy Museum and the memorial around lynching sit in a place where that narrative structure is in the built environment, you [00:16:00] know? But it's not about overcoming, it's about sitting with something, you know? What does it mean to sit with the violence? I remember, I write about this in the book, people looking at all of those jars of dirt.

Lee: A quick note here. For years, the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama has been collecting jars of dirt from the thousands of sites where Black men, women, or children were lynched throughout the 20th century or the last years of the 19th century.

It's an overwhelming, haunting display. Thousands of jars filled with dirt that bore witness to the violence.

Eddie: Trying to find, I think, you know, the county where they may have had a relative lynched.

You know, I, I just, I'll tell this story really quickly. I'm working on a book, it's not gonna be out for a while, and no one knows this, about Mississippi, and I'm organizing it around these deaths.

And [00:17:00] my research assistant found someone who was lynched in Pascagoula, Mississippi, where my dad grew up, where I went to church, who was lynched in June, June 21st, 1899. And they said he was buried in the colored cemetery of Creole Town. And that's the name of the cemetery of my Catholic church that I grew up in.

So there's a lynching at the heart of our comm-- he was hang-- he was lynched on, at the old Hangman's Oak. And there's this-- what does it mean to grapple with that moment, to confront-- And I, and no one in my church knew, 'cause I grew up Catholic on the coast of Mississippi. No one knew anything of this. And so what does it mean to have this moment at the heart of our community, in some ways?

So what the lynching memorial forces us to do is not look for the, search for the [00:18:00] comfort of the Civil Rights Act of '64, the Voting Rights Act of '65, or the soaring rhetoric of the March on Washington of '63. No, it forces you to sit in the horror of the violence itself.

And I've been doing that, Lee, for, for a while.

Not in a pornographic way, but trying to understand the intimacy of the hatreds. 'Cause when you, when you look at the images of it, the postcards, and you see the cruelty and the barbarity, the cannibalism of it. When I teach the rituals of lynching in my religion classes at Princeton, I, when I say, the cannibalism of it, the students are like, what do you mean?

And it's like, well, you know, if you smell something, what happens? You taste it. [00:19:00] So what does it mean to be around burning flesh? You're gonna taste the flesh.

But beyond the cruelty of it, you see children, you see families, you know, it's something else happening besides-- the violence is an occasion for something else to be consolidated, to be affirmed, to be protected in some ways.

I just saw the movie, the film Till, and I said, you know, the people knew who killed Emmett Till. They knew who threw him in the Tallahatchie River because they played checkers with them. They drank beer with them. They talked about it.

It's the intimacy of [00:20:00] it all. And I think what that experience in Montgomery, intentional or not, what it did for me is to kind of throw me squarely into that.

Lee: Yeah, I mean, one of the first things I did was go look for-- I was raised in Alabama, Talladega, Alabama, and so the first thing I did was go look for Talladega County. And I had no idea that four people had been lynched in Talladega.

Eddie: I didn't eith-- I went to Jackson County. Didn't have any idea. Yeah.

Lee: Yeah. You note in your book, or maybe in the, the lecture I watched, that discussion of the Civil Rights Movement wasn't something that you were raised on all that much, and didn't really start engaging it until maybe a sophomore in high school.

For me, it was not until I was in seminary, so I was early twenties, and one of my professors had us watch some of the Eyes on the Prize series. And it was the segment on the Freedom Riders.

Eddie: Oh yeah.

Lee: And the bus that got firebombed.

Eddie: Yeah, in Anniston, Alabama.

Lee: And I realized-- and I started figuring out where it [00:21:00] was on the highway, and I realized, this was like 10 miles from my house.

And I had never heard that story about that bus being firebombed until I was in seminary, away from Alabama. And so as I've, through the years, have taken students on trips, read, continue to read, I think one of the things that it's done for me, just as a person, is I feel as if it's helped me better understand who I am. And it was as if I was blind to a lot of realities about who I am.

Eddie: Mm-hmm.

Lee: And I hear you inviting us to that same sort of difficult work of looking at who we are, looking at our lineage, looking at our traditions, and only by looking at something that makes it really, really difficult to acknowledge or look at or confess, can we even begin to understand really who we are.

Eddie: Yeah, I mean, in some ways it's an Emersonian project, right? I mean, when we think about Emersonian perfectionism, it's this reaching for a higher self, right? This, you know, leaving [00:22:00] oneself behind in order to reach for a higher self as you climb the ladder. But, you know, for, for, for Black folk in this country, life ain't been no crystal stair.

But what does it mean to reach for a higher self when you haven't come to terms with the old one? It means you're stuck. If you don't really engage in the kind of self-reflection to understand that which you leave, which you're supposedly or purportedly leaving behind, then you never do. You end up carrying your sins forward, which we've done generation after generation after generation.

Lee: So let me ask a little bit about both Baldwin and your own engagement with being grounded in, out of, the Christian tradition.

Eddie: Sure.

Lee: Uh, because, you know, e-- even in, in your book, you point to Baldwin, speaking of bearing witness, the new Jerusalem, and in your own [00:23:00] lecture on Medgar Evers that you recently did, you speak of how, and just as an admission of the fact that you are a sinner grants the possibility that you'll be saved, in the same way must Americans look at their past and their, and the sins of the past if we have any hope of moving forward.

And I'm sure the examples could be multiplied. But how, how do you think about a Catholic being raised in Mississippi, in what ways has that rootedness, that tradition, fueled and formed, assisted, and in what ways have you found it to be a hindrance or difficult?

Eddie: Yeah, that's such a great question, Lee. I haven't been asked that question in a long time.

So I was raised Catholic on the coast of Mississippi. Our church, St. Peter's Apostle Catholic Church was the first, uh, Josephite mission on the coast of Mississippi. So I, you know, grew up in a, a Black Catholic church. I remember seeing St. Martin de Porres over on the side.

But I went to Morehouse. [00:24:00] And by going to Morehouse, I was literally baptized in some of the, some of the deepest Baptist waters you could imagine, listening to some of the most extraordinary preaching in the world. I can, I can literally remember hearing Gardner Taylor, and my mouth just fly-- 'cause I had never seen anything, heard anything like this before.

And so my moral languages are bound up in those two critical formations. So growing up Catholic is a sense and attentiveness to ritual, a community.

Lee: Right.

Eddie: You know, they say you can never stop being Catholic. You just lapsed.

[Lee laughs]

You put me, you put me in Mass and I'll immediately be able to, to say the confession of faith, I could do all that stuff. Ask me now, I'll stumble.

Right, but there's something about a sense of community. And, and there's also, I think, as a scholar of [00:25:00] African American religion, understanding the importance of, of Christian-- Black Christianity as a space for the emergence of Black civil society.

So my moral languages are bound up with those narratives, those stories, my ethical orientation shaped by, right, the lessons gleaned, uh, the precepts understood and learned from those moments.

And so even with Baldwin, you know, he says, "I left the church, but the church never left me." And so there's a sense, in order to understand his sentence structure, you know, it's not only Henry James, it's not only Proust, it's the King James Bible.

You know, he's a preacher at the age of 14. Pentecostalism shapes his imagination in certain ways. So there's a way in which you read him, you can see a certain homiletic tradition shaping just the structure, the formal structure [00:26:00] of his essays.

And when he invokes love, you know, it's, it's, it's not just agape for Baldwin, of course. It's philia, it's eros, but love language, you know, that's deeply Christian. You know, it's, it's not like he's taking the languages of the Jewish New-- New York intellectuals that help formed him, and that's in-- No, no. This love talk comes straight out of this form of, of Christianity.

And see this-- and I say this form of Christianity because the adjectives matter.

The great theologian Howard Thurman said, "These slaves dared to redeem the religion profaned in their midst."

They wanted to rebuke what is called white Christianity as idolatry. That this commitment to this racial ideology, right, segregates pews, [00:27:00] segregates the gospel, segregates heaven. That's not the teachings of Jesus.

Baldwin is coming out of that tradition, even as he's being critical of it, you know, 'cause he says in that last-- that, that extraordinarily provocative line in the transition in his 1963 text, uh, The Fire Next Time, and I'm paraphrasing, if God doesn't make us more loving, if God doesn't make us more expansive, you know, then it's time we got rid of Him.

And of course a lot of people raise their eyebrows at that one.

Lee: Yes.

[Both laugh]

So, myself, I'm somewhat suspicious of any kind of essentialist arguments about religion or any given tradition, and so I wanted to couch this question in a way that I don't fall prey to kind of asking an essentialist sort of question.

But when you think about how does Christianity as a tradition give rise to-- you know, what Willie James Jennings has done such a great job of showing the way back to the 15th century, it creates the myth of race that becomes such a horrific power in the world. [00:28:00] And that same sort of Christian tradition gives us atrocious forms of imperialism, colonialism, and so forth. And then finally, the, the, the white Christian experience in America.

So that's one form of Christianity. And then you have, um, a form of Christianity that you're just pointing-- that, that Baldwin is, is pointing us to, that in some of the Black Christian experience, it redeems this Christian tradition that has been profaned in its midst, which is a beautiful line... powerful line... troubling line.

What are the steps by which one ends up in one or the other of those?

Eddie: Yeah, I mean it's one of the interesting features of, you know, that moment with Martin Luther, right. Our relationship to the gospel doesn't, does not require mediation. So if sola scriptura is serious, that means we're gonna get a proliferation of interpretations.

What happens when a person who is [00:29:00] experiencing brutal domination, cruelty that is unimaginable, in the context of slavery, even if it's a small group of two or three or a huge plantation, come across a line that is being preached, that God is no respect of persons?

Lee: This line, "God is no respecter of persons," comes from a pivotal moment in the King James Version of the New Testament in Acts 10, in which the apostle Peter has just had a sort of second conversion experience, realizing that the old lines between what had been considered clean and unclean, the old lines between people who are included and people who are not, had been abolished.

Eddie: And here you have, this is one of the ironic moments, right? Here you have a, a slave who's heteronomous, who's being treated as an, as a means to someone else's [00:30:00] ends - literally, a piece of property - finds within the gospel, through the relationship of human being to God, a way of disrupting a relationship between slave and master.

Oh, you may be my master on earth, but I have a-- and then that becomes the condition for, for imagining a different kind of self. But it all, it all has something to do with what, what human beings bring to the text, what we bring to this extraordinary tradition that carries with it a host of examples of the depravity of, of human beings and the miraculous nature of human beings, you know?

Baldwin has this wonderful line, Lee. He says, you know, "We're at once-- you know, excuse my language, you know --miracles and sons of [bleep]."

[Both laugh]

And it's evident-- and it's evident in our--

Lee: That's a good word.

Eddie: And it's evident in our interpretations.

Lee: Right, right.

So I [00:31:00] hear, so I hear, I hear you saying there - so correct me if I'm wrong - but what I hear you saying there is that... because at first when you started down that path, I thought, well, that's just, just like a Catholic, to lay it, lay it at the feet of the Protestants.

[Eddie laughs]

But what I, what I hear you saying there is that, is like, in, in the Protestant tradition with our individualism and our individual encounter with Scripture, we're gonna end up with lots of different possibilities.

The slave can end up with something very different than the slave owner, right? But clearly this issue is not a Protestant issue in terms of the Spanish conquistadors, right?

Eddie: No, not at all.

Lee: It is a Catholic sort of thing as well.

Eddie: Not at all.

Lee: Um--

Eddie: And then you have, within the Catholic tradition and within the Protestant tradition, these prophetic voices offering a different interpretation.

And remember, the prophetic voice is always in the minor key.

Lee: Right.

Eddie: Has always--

Lee: Yeah, you have Bar-- what, Bartolomé de las Casas, right, who's, uh, proclaiming, can you not see what you, you're--

Eddie: Complicated dude.

Lee: Right. Yeah, yeah.

So, I want, I want to hit this real quick.

Eddie: Sure.

Lee: Because I think it's an important point. Tell us why the [00:32:00] phrase 'Make America Great Again,' or Reagan's rhetoric about the city on a hill are forms of 'The Lie.'

Eddie: Yeah. So the phrase 'Make America Great Again,' right, is laden with a whole set of assumptions about ideally what America consists in.

So each time the phrase has been invoked, it is in response to attempts to imagine the country anew. So 'Make America Great Again' is a kind of nostalgic longing for a time before the Civil Rights Revolution, right?

Reagan is in '80. You know, twelve years after the passage of the last piece of-- a major piece of legislation of the Great Society, the Fair Housing Act of '68. He's elected in '80 to undo it all. [00:33:00] And so the appeal to making America great again has everything to do with the forgotten Americans, the silent majority, has everything to do with, you know, responding to the barbarians at the gate.

And the same thing with its, you know, its, its echo In the Trump world. The city on the-- Reagan adding the, the adjective 'shining' city on the hill, is an attempt to sacrilize a project, to sanctify it, to give it the imprimatur of God.

And in doing so, it secures it from critique, right? What does it mean to challenge the idea that America is the shining city on the hill? Right? It's, in some ways lead to challenge the idea that we were divinely chosen, that we are the chosen people of God, the chosen nation of God. [00:34:00] And Chosenness is an ideology that, of course, aims to conceal and hide our ugliness and to justify, at times, the slaughter.

Lee: After a short break, we'll come back to discuss why so-called 'colorblindness' is not a helpful response to racism, and what it might look like to continue James Baldwin's work of finding ways to consistently begin again.

So one of the major moves that you develop numerous times in the book is the way in which Baldwin's earlier hope about the possibilities for the American project began to be so deeply [00:35:00]challenged, if not undone, by the betrayals of the '60s.

So could you kind of quickly point us to-- what, what are some of the kind of concrete personal, his own encounter with what he's experiencing as this undoing of hope and how that comes around to such anger in him?

Eddie: Yeah, I mean, I think, quickly, it, it has everything to do with, he's watching what these young people are experiencing in the South. Baldwin, I think he was a member of CORE. I mean there-- he certainly was fundraising for CORE.

He supported Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. He was more actively connected with those organizations than King's, SCLC. He witnessed up close what these young folk had experienced.

As early as 1964 with Blues for Mister Charlie you could begin to hear-- which is a play based on the, the lynching of Emmett Till. You can begin to hear the anger and the rage. You begin to see elements of transition.

Or even the, the assassination of Medgar Evers in Mississippi in, you know, in '63. So, [00:36:00] so you, you hear it, but it was the assassination of King in '68... If you can, if they could murder the apostle of love... my God.

And so I say it, you know, although you can chart, you can track it earlier, I say this with the-- 'cause he says something happened in that moment in him, this very structure, the nature of time fractured post King's assassination, for Baldwin.

Tried to commit suicide. Had everything to do with a failed love affair on, on one hand, but also the moment.

And at that point he's like, I don't know.

You know, the advice he gives to his nephew, that we have to love them so that they can see themselves differently. They're gonna have to get themselves together, right? We are going to have to continue to fight for the new Jerusalem, but they are going to have to get themselves together.

And so in my own work and in my own public speaking, I'm always playing with 'we.' [00:37:00]You'll see, I use 'we' all the time in various ways because that transition is not hard and steadfast, but it happens.

Lee: So the 'we' earlier being a 'we' that included helping whites come to terms with what they needed to change, and then, and subsequently it's, 'they' have to get their own stuff together.

Eddie: It's multi-- it's multilayered. So at one moment the 'we' is us. Another moment the 'we' is just Black folk. Another moment is an aspirational 'we,' the we to which we aspire. Right?

And so-- and then there's a moment where he inhabits the voice of white America. When you read "Many Thousands Gone," the viewpoint of, of that essay is he's actually talking as if he's, he's a white man in that moment. And so it's this playing on the 'we,' where the 'we' kind of blurs. We becomes us, becomes them, becomes, you know, mine, you know, I, in that way.

[00:38:00] And so it, it has a kind of moral character to it, or quality to it in some way.

Lee: So then, after King's death, he begins to be much more public about public understanding of the Black Power Movement, Black Panthers, and the possibility of violence. So kind of, kind of fill that out for us?

Eddie: Yeah. I mean, you know-- and this is really important in terms of the story we talked about, the typical historical narrative around the Civil Rights Movement. It's, it's, you know, Civil Rights tourism is progressive. The story of the Black freedom struggle is actually often narrated as a narrative of decension.

You get the high point of '63, usually starting with Emmett Till's murder, '54. Brown v. Board, '54. Mont-- Montgomery Improvement Association boycott, '55. Student sit-ins, April of 1960. King's March, 1963. Somebody might throw Selma in there, and then King's assassination in '68. That's it.

'65, '66 represents a moment of decline. Why? It's the Freedom Against-- March Against [00:39:00]Fear. Stokely Carmichael declares, "No more 'Freedom Now,' we want Black Power." October 66, Black Panther parties organized in, in Oakland. Here's all of this anger, rage. '65, Watts explodes. '68, hundreds of cities are exploding after the murder of Dr. King. And so Baldwin's in the midst of this. And his, his, his point is to say, these are your children, all of these people.

And so when we draw that hard line between Black Power and the Civil Rights Movement, we don't understand that many of the young people who were shouting Black Power were also the young people in SNCC, in Selma, Alabama, in Mississippi, in Georgia. Stokely Carmichael said he never broke nonviolent discipline except for one time, when a policeman attacked King.

Right? And so Baldwin at this moment isn't, kind of, buying into this kind of, what he called "this mystical Black bull[bleep]." I mean, he thought Black [00:40:00] Power, assuming this essentialist notion of Black, it was nonsense, right?

But he wanted us to understand the nature of the rage, the nature of the anger. The rage lights the kiln. But it's not sufficient. It's necessary.

Lee: So I want to, I want to come back to that when we, when we end, but before we get there, the notion of, you know, it is still common-- you know, I, I'll still hear, among white folks in, in the South to speak, um, in sort of idealistic terms about being colorblind, right? And yet you're, you're pointing us with Baldwin to this sort of notion, it's much, much more complex than that.

So could you kind of-- for those who are, who might be listening and think, well, why isn't it as simple as being colorblind? Because I, I think there's still a lot of assumption that that is the answer. But could you talk about that a little bit?

Eddie: Yeah. So really quickly, you know, I, I'm gonna talk about it.

I talk about it as I travel around the country. We have to understand [00:41:00] how the value gap organizes our world. We have built the country true. The vaunted American middle class came into existence as a result of New Deal policies that denied Black folk access.

Lee: Which I guess is also one of the largest ways in which the middle class has, uh, what, conglomerated wealth of anything that's happened in the last hundred years, right?

Eddie: Exactly. So if you see, if you see how the FHA loans were distributed, which allowed white Americans to buy homes, which then allowed them to accumulate wealth, Black folks systematically locked out of those FHA loans and then pushed into communities that were redlined and then devalued.

The wealth gap is not something that-- the wealth gap didn't result from Black people's inability to, to, to save. It has everything to do with policy.

We can talk about education in terms of segregated schools and funding. We could talk about housing, the dual housing market, a dual labor market. Policy [00:42:00] built the country. We were deliberate.

And if we're going to build a multiracial democracy, we're gonna have to be as deliberate in dismantling it as we were in creating it. And colorblindness doesn't allow us to be deliberate. It literally allows us to turn our eyes away from what we've done, and to assume that we can all just, from now, move forward and not address the cumulative effect of generations of a society organized along the lines of the value gap.

So colorblindness as an aspiration makes sense, but as a remedy, [00:43:00] it actually deepens inequality in the country, to my mind.

Now, that's hard to make that argument when people are thinking in a zero sum way, because if we're not colorblind then I'm gonna lose because we're gonna have to do something with these folks, if in order to be just, racially just, we have to give up something. And my response to that cuts a little deeper.

They have us all believing that the pie is only so big, when in fact all of us should just simply be yelling, "bake a bigger [bleep] pie."

Lee: Hmm. Hmm.

So when, when you think about your own experience, and it brings us back to the, the title of the book, Begin Again--

Eddie: Yeah.

Lee: Have you had encounters where you've, you've wanted to abdicate responsibility and just be done with [00:44:00] this? But what's it look like for you personally to encounter Baldwin's call to continue to begin again?

Eddie: You know, I've been grappling with this in another book I'm working on, which is coming out before the 2024 elections. The last interview in 198-- November of 1987, the month before he dies, Baldwin's exhausted, not only because ca-- cancer is ravaging his body, but you know, he, he saw Reagan coming. He saw what they were gonna do.

And he says, you-- he has this wonderful sentence, you know, you can only go to Texas so many times. And he says, I felt like a broken motor. And I saw it. I saw what they did. I saw the choices that they made, that they were making. You still had to bear witness.

But in this moment, which feels like our moment now, feels so profoundly wrong, [00:45:00] I'm, I'm trying to hold off a sense of madness and rage, right?

Because I'm thinking, oh, here we go again. And another generation, another generation of Americans, Black and white and brown are gonna be-- their characters are gonna be disfigured, you know, distorted by this nonsense. And you just wanna scream.

And then you gather yourself, in my case drink a little Jameson, dust your-- dust your knees off, and join the fray.

So you know, 'cause Baldwin-- that line about 'begin again' comes after a description in the novel of what happened in the aftermath of the Civil Rights Movement. Some people were arrested, some people were dead, some people went mad, some people left the country.

Responsibility is not lost. [00:46:00] Responsibility is abdicated. And if you refuse abdication, then you begin again.

Yeah.

Lee: To tie us up, then, you quote Baldwin saying, "There's absolutely no salvation without love. This is the wheel in the middle of the wheel. Salvation does not divide, salvation connects, and in you. In the end, we cannot hide from each other. When we imprison our fellows in categories that cut off their humanity from our own, we end up imprisoning ourselves. We can't hide behind the mask either. We have to run toward trouble. That makes us afraid of life."

Any, uh, closing comments on that, those beautiful lines?

Eddie: Thank you. I, I still believe in them. Even in my darkest moments. Salvation is in the going towards.

It's in the going towards.

Lee: [00:47:00] Been talking to Professor Eddie Glaude from Princeton University. Thank you for honoring us, both with your time and honoring us with your work in the world. And, uh, we're privileged and grateful to be with you today.

Eddie: Thank you. I appreciate you.

Lee: You've been listening to No Small Endeavor and our interview with Eddie Glaude, one of the nation's most respected educators, political commentators, and public intellectuals, on his book Begin Again: James Baldwin's America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own.

We gratefully acknowledge the support of Lilly Endowment Incorporated, a private philanthropic foundation supporting the causes of community development, education, and religion, and the [00:48:00] support of the John Templeton Foundation, whose vision is to become a global catalyst for discoveries that contribute to human flourishing.

Our thanks for all the stellar team that makes this show possible. Christie Bragg, Jakob Lewis, Sophie Byard, Tom Anderson, Kate Hays, Mary Eveleen Brown, Cariad Harmon, Jason Sheesley, Ellis Osburn, and Tim Lauer.

Thanks for listening and let's keep exploring what it means to live a good life, together. No Small Endeavor is a production of PRX, Tokens Media, LLC, and Great Feeling Studio.