TOKENS PODCAST: S4E11

“If I can’t dance, then I don’t want to be part of your revolution.” This quote from political activist Emma Goldman hangs in the office of Ben Cohen – the “Ben” in Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream. In this interview, Ben and Lee discuss why the work of justice requires a disposition of light-hearted hope and good humor, and how the business of ice cream has been the perfect avenue for Ben’s work for peace and activism. As he puts it, “It has to be the joyful journey for justice. Business's most powerful tool is its voice, and so we'd been trying to use that voice for justice.”

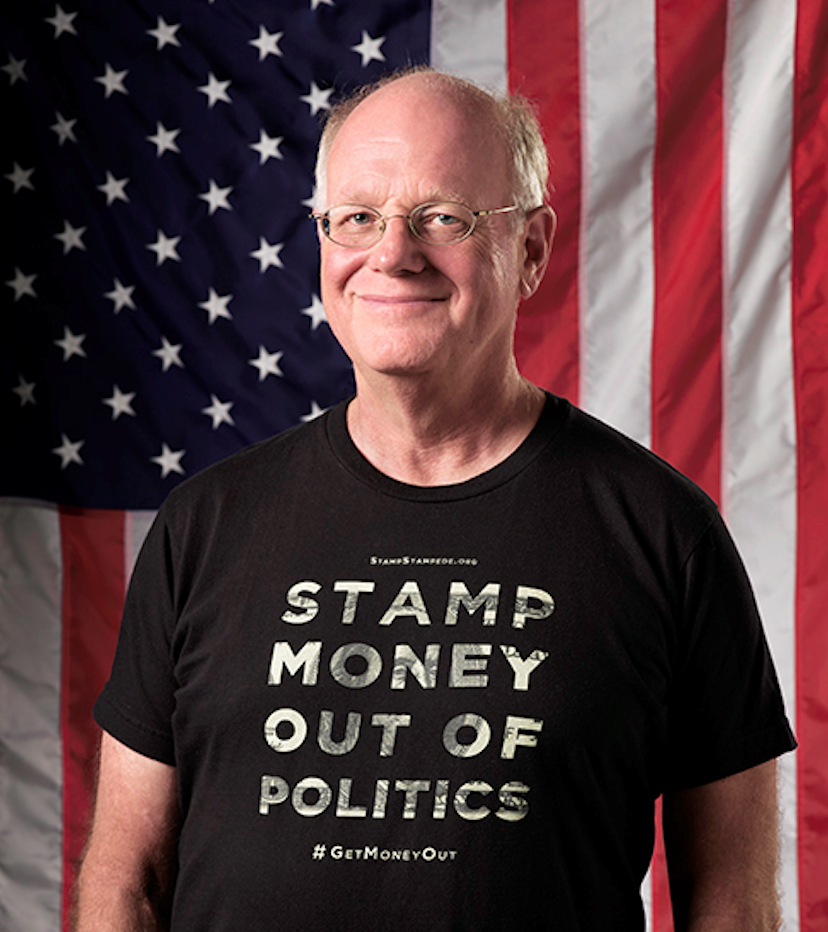

ABOUT THE GUEST

Ben Cohen was born in Brooklyn in 1951 and brought up in Merrick, NY. In 1978, he and his longtime friend, Jerry Greenfield, started a homemade ice cream parlor in an old gas station in Burlington, Vermont. The ice cream was well received and after a few years, Ben & Jerry’s started to distribute pints to grocery stores in New England and eventually nationally and internationally. Along the way, Ben held the positions of scooper, crepe maker, truck driver, Director of Marketing, Sales Director, CEO, and Chairman of what became a $300 Million-a-year public corporation.

In 2000, despite his efforts to keep the company independent, Ben & Jerry’s was sold to Unilever.

Ben and Jerry have received numerous awards and recognition, including the Corporate Giving award from the Council on Economic Priorities, the US Small Business of the Year Award from President Ronald Regan and several honorary doctorates.

Along with Jerry he authored the book, Ben & Jerry’s Double Dip: How to Run a Values-Led Business and Make Money, Too.

Ben has served on the boards of the Social Venture Network, Hampshire College, Oxfam, Greenpeace, Business for Social Responsibility and Heifer International. In addition, Ben also served as the National Co-Chair of the Bernie 2020 Campaign.

Currently Ben divides his time between AssangeDefense.org, @DropTheMic2020, working to end qualified immunity, and eating ice cream.

ABOUT TOKENS SHOW & LEE C. CAMP

Tokens began in 2008. Our philosophical and theological variety shows and events hosted throughout the Nashville area imagine a world governed by hospitality, graciousness and joy; life marked by beauty, wonder and truthfulness; and social conditions ordered by justice, mercy and peace-making. We exhibit tokens of such a world in music-making, song-singing, and conversations about things that matter. We have fun, and we make fun: of religion, politics, and marketing. And ourselves. You might think of us as something like musicians without borders; or as poets, philosophers, theologians and humorists transgressing borders.

Lee is an Alabamian by birth, a Tennessean by choice, and has sojourned joyfully in Indiana, Texas, and Nairobi. He likes to think of himself as a radical conservative, or an orthodox liberal; loves teaching college and seminary students at Lipscomb University; delights in flying sailplanes; finds dark chocolate covered almonds with turbinado sea salt to be one of the finest confections of the human species; and gives great thanks for his lovely wife Laura, his three sons, and an abundance of family and friends, here in Music City and beyond. Besides teaching full-time, he hosts Nashville’s Tokens Show, and has authored three books. Lee has an Undergrad Degree in computer science (Lipscomb University, 1989); M.A. in theology and M.Div. (Abilene Christian University, 1993); M.A. and Ph.D. both in Christian Ethics (University of Notre Dame, 1999).

JOIN TOKENS ON SOCIALS:

YOUTUBE

FACEBOOK

INSTAGRAM

JOIN LEE C. CAMP ON SOCIALS:

FACEBOOK

INSTAGRAM

LEE C. CAMP WEBSITE

TRANSCRIPT

Lee: This is Tokens. I'm Lee C. Camp.

It's no secret that higher education in these United States--especially in the grad school arena, and especially in the humanities--is an exercise in so-called consciousness-raising: you get exposed to so much about the world that's screwy, unjust, oppressive, and downright rotten. It can be rather, well, depressive.

I'm thinking now of a young professor who was new on the faculty in my own heady days of grad school. He actually looked quite a bit like the brilliant Robin Williams. I had just met him for lunch. And I had just concluded some melancholy commentary upon the state of the world, and he gave me a friendly slap on the shoulder and said, "don't take yourself too seriously, Lee. You gotta keep a sense of humor."

I always admired the way this professor seemed to be able to keep a sense of humor, not take himself too seriously, even while he was working and writing on terribly serious matters.

This summer, Laura and our three sons--Chandler, David, and Ben--made our way to lovely Vermont, staying in a friend's early 20th century beautiful farmhouse for a few weeks. It was a delightful respite from Nashville's late summer heat-and-humidity which, if you've not experienced it, you should. Just so you can know that if the Catholics are right, that you don't want to have to spend too many years in purgatory.

But while getting ready to make our way to Vermont, I happened to remember that my buddy Shane Claiborne is friends with Ben Cohen, who is the -Ben- in Ben & Jerry's Ice Cream. And one thing led to another, and next thing I know, I'm booked to go to Burlington to interview Ben.

I found myself kinda, giddy really, strangely so, about interviewing a former ice cream company CEO. And the more I read about him, the more excited I got about it. Because here it was: someone who has refused to take himself too seriously, who's kept a rather delightful sense of humor, and done so while taking quite seriously the work of justice and fairness and equity.

And he's done all that through -ice cream-.

Ben: you know, there's a quote up on the wall of my office that says: if I can't dance, I don't want to be part of your revolution.

Lee: So, there you have it: a recipe for revolution: it's justice and ice cream.

Ben: Yes, it's got to be fun. It's got to be the joyful journey for justice.

Lee: Ben's ice-cream royalty has afforded him a platform to be a voice for many causes, including police reform, reduction of the military budget, ethical business practices, and much more.

Ben: We realized that if we could figure out a way to integrate social, social concerns into our day-to-day business activities, that would be way, way more powerful. Business's most powerful tool is its voice and so we've been trying to use that voice, for justice.

Lee: A delightful conversation full of laughter, stories, wisdom, and ice cream, coming right up.

INTERVIEW

Lee: Ben Cohen was born in Brooklyn in 1951, brought up in Merrick, New York in 1978. He and his longtime friend, Jerry Greenfield started a homemade ice cream parlor at an old gas station in Burlington, Vermont, that they painted orange.

Ben: Grossman's orange, right.

Lee: The ice cream was well received. And after a few years, Ben and Jerry started to distribute pints to grocery stores in New England and eventually nationally and internationally. Along the way Ben held the position to scooper crate maker, truck driver, director of marketing sales director, CEO, and chairman of what became a $300 million a year public corporation. In 2000, despite his efforts to keep the company independent Ben & Jerry's was sold to Unilever.

Ben and Jerry have received numerous awards and recognition, including the corporate giving award from the council on economic priorities and the U.S. small business of the year award from president Ronald Reagan and several honorary doctorates. Delighted to be here today with Ben Cohen. Thank you, Ben, for the invitation to come be with you.

Ben: Good to be with you.

Lee: Here in beautiful Burlington.

Ben: Indeed, we are.

Lee: The beautiful town.

Ben: Yeah. Capitol of our State, it’s the biggest city in the State, all 30,000 people.

Lee: Wow. That's the largest city in the State. Yeah. That's about the size of my hometown. A little larger than the size of my hometown in Alabama. But nestled here on the shores of Lake Champlain, you look across Lake Champlain and see the beautiful Adirondack Mountains in upstate New York.

And it's just a beautiful place.

Ben: Thank you for setting the scene.

Lee: Yeah. Thanks so much for having us with you. I must say, on, uh, on social media, I put out a message last night that was going to get to interview you today. And there are a lot of people have a lot of opinions about you, Ben. And there were some who just really wanted me to let you know that they really wanted you to bring back Wavy Gravy.

Ben: You know, there's so many people that are very vocal about bringing back Wavy Gravy.

Lee: John Gunner's wife loves Fish Food, Susie Cox and Ali Aber, Chunky Monkey, uh, Cherry Garcia from Corey Wiser. Fain Spray, a vocalist in Nashville, she said, tell him that Berry Mascarpone literally changed my life.

Ben: Alrighty. Well, that's good to hear, happy to be of service to your taste buds.

Lee: Yeah, in so many ways. So, but not only, I suppose, to people who have strong feelings about your, ice cream flavors, but you've been one of the few businesses in the United States has been forthright about being politically active for progressive social causes from the very start. And what got you going down that road?

Ben: Well, at the very beginning, you know, we were just a little homemade ice cream shop. And we were active in our community. We were sponsoring community events, et cetera. But as the company got larger, we realized that we had a platform that people were willing to listen to what we had to say.

And we felt like if people were going to come to talk with us, we would talk about what's really important. And, I know it's a little hard to believe, but some things in life are more important than ice cream.

And, we kind of believe in justice and we also believe that, he, who is silent consents, you know. What you hear a lot now is that white silence is violence.

And, I believe that's true. And so I, I feel like when you become aware of situations of injustice, you can either ignore it. You can complain about it, or you can do something about it.

Um, I feel a lot better doing something about it. We've been doing something about it through the best platform we have, which is Ben & Jerry's, and, I've been really happy the way we've been able to integrate social concerns into our day-to-day business activities. So that's, kind of how it started.

Lee: So recently, I want to talk about as we get to them and a number of things that you've gotten involved in, but your most recently published book Above the Law: How “Qualified Immunity” Protects Violent Police. For those who aren't aware, could you just kind of give a definition of qualified immunity?

Ben: I think the best definition is that, you know, if I haul off and punch you in the face, you can sue me. If a policeman does it, your case will be thrown out of court because police have you know, this judicial doctrine called qualified immunity. And essentially what qualified immunity says is that if a cop commits an illegal act, if the cop violates your constitutional rights, that cop will get off scot-free unless there was another cop in the past, in the same jurisdiction who had done essentially the same thing and gotten convicted. Then, you could actually sue the cop, but if not, the cop gets away with it.

Lee: So the more general legal principle of a suit based upon violation of constitutional rights in effect is, inconsequential in these cases.

Ben: It's thrown out by the judge unless the victim can show that, essentially exactly the same thing happened previously in exactly the same jurisdiction and the cop was convicted.

Lee: Now how did such a law, or principal, come to be?

Ben: It’s pretty interesting how qualified immunity came to be. It's based on an interpretation of, a federal law that was passed during reconstruction.

What happened was that in the South a lot of the police were still members of the Ku Klux Klan. And they would brutalize and abuse Black people. And so the federal government passed a law specifically stating that if an employee of the state, a policeman, violates your civil rights, you can sue that policeman personally in court.

And that worked well for a while. And then there was a Supreme court decision that essentially undermined that law. And it said that, well, the only circumstance in which you can sue that cop who violated your rights is if there had been a previous case where a cop had been convicted.

I mean, the theory of it is that a cop, otherwise known as a law enforcement officer, is not expected to know the law. Think about that. And so what this judicial doctrine said was the only way you can expect a cop to know something's illegal is if another cop was previously convicted for doing that illegal act. It doesn't make sense. It's crazy. It's absurd. And it is the reason why we see so many examples of police abusing, going so far as to murder on our Black people, and getting away with it.

Lee: What y'all give in your book, I think 16 different cases, and they're shocking cases and a remarkable, any of those in particular, stand out to you, any particularities of those?

Ben: You know, the one that, I don’t know, just really sticks in my craw. I mean, there's a lot of them, but, the one that somehow stood out to me is the case of David Collie. There's these two policemen, off-duty cops in an unmarked car, that hear a call on their radio, saying that, there's these two tall black guys that stole some sneakers from someone. One of them might've had a little silver pistol, and, they get this call and they happened to be at this apartment complex and they see someone who does not at all fit the description, except that he's male and black and they yell out, uh, hey, what are you doing there?

Uh, where are you going? And the guy points to the apartment that he's walking toward and they ended up shooting him in the back, paralyzing him for life from the chest down. And on top of that, they then go and fill out a report saying that David Collie assaulted them and they ended up handcuffing him. He's handcuffed to his hospital bed.

And, eventually the dash cam footage comes out showing that the guy was shot in the back, that he was nowhere near these officers. And he sues the officers because, you know, they, paralyzed him for life for no reason. He did nothing wrong. And the officers get off scot-free because, well, there was not an example of that exact same thing happening before in that jurisdiction.

And that's well, that's what he's got to live with for the rest of the slide.

Lee: Just for those who are listening, I do think that I would point people back to the book Above the Law, because you had 16 cases, I think, that sell very similar stories, some of which end up in death, but these sorts of kind of grotesque examples of abuse, and then simply get thrown out of court because of the principle.

So one of the things that's striking to me is that you've got the ACLU on the stereotypical left end. You've got the Cato Institute on the stereotypical right end. You've got both Justice Sonia Sotomayor on the left, Clarence Thomas on the right. Different ends of the spectrum are critiquing this principle.

And yet it still has such sway in our legal system.

Ben: Yeah. People on the left and the right all believe in justice and rationality.

It's been really amazing for us working with, the Cato Institute, uh, the Institute for Justice, Americans for Prosperity, which is a Koch funded organization.

I mean, these are organizations that we don't usually work with. We’re usually, you know, fighting them on the other side. And it is really great to find an area of common ground and area of agreement. And it just based on basic justice and reason and rationale.

Lee: When you face an issue like this, that seems so exasperating, how do you process that internally? What do you do with that kind of exasperation?

Ben: I keep on working at it and plugging away on it. I mean, this is about shifting from protest to policy. Protest, is hard. I mean, you got to stand up for what you believe in, you know, you got to show up, but, the protest is over. You know, I mean, you do the protest and you move on. The long heart slog is changing the policy, making it so that the protest was worthwhile. I mean, if you just protest and nothing happens, nothing changes that ain't going to work. So we got involved in this because, we felt like qualified immunity is really, the key to reforming police behavior because it's focused on accountability.

And as business people, you know, Jerry and I learned time and time and time again, that the only way to get an organization to perform the way you want it to is to hold people accountable.

I mean, at Ben & Jerry’s we could say, well, there's particular workplace rules. You have to do things according to a particular procedure.

But if we don't hold it people accountable when they don't follow that procedure, that sends a very strong message to the organization. It says, well, this is just lip service. It says, well, they don't really mean this shit. And there's no consequence if I violate the rule or regulation.

And it tells people throughout the organization that you don't really have to abide by that rule of regulation.

Lee: Yeah. Yeah. You've been, I would guess, especially with this particular issue, have you been critiqued for being anti-police?

Oh, very much. We've been very much critiqued as being anti-police and, it's not true.

I mean, we believe that it's necessary to have police in a society, but you can still support the idea that yes, we should have a police force, but no, they should not brutalize people and they should be held accountable. And that's the amazing thing that, you know, police, they're happy to talk about reform.

They're happy to have different regulations or whatever, as long as you don't hold them accountable. And that's the key. So that's what we're trying to do is to have some accountability. I mean, why should law enforcement officers be above the law? For regular people, we are brought up with the understanding, people drumming into our heads, ignorance of the law is no excuse. We all know that.

Why the hell should it be different for a police officer, for a law enforcement officer to be above the law?

Lee: Thinking about critique, given all the sorts of sociopolitical work that you've done, I would imagine. And I know of, cause I've read about some of it, some of the critique that you've come under. One of the favorite questions I've liked asking public figures is what sort of toolbox have you developed to deal with critique?

What sort of practices or habits, or how do you deal with it?

Ben: I just, I expect critique. I mean, that's part of taking a stand and, if the stand that you take does not generate criticism, there was no need to take the stand to begin with. I mean…

Lee: That's pretty, that's pretty great. That's pretty great.

Ben: If everybody already agrees with you, I don't need to say anything about it.

Lee: That's really helpful. Yeah, it's definitely one of those things that, you know, I think those of us who were raised as Southern Christian gentlemen and who were sometimes taught by our preachers that Christian love means being nice, makes some of that hard for us in some of these States.

I wonder just kind of culturally how, it seems to me that New England, Northeast, y’all seem to do so much better at laying things out there and being okay with sort of sparked exchanges than maybe we are in the South. I don't know any observation about that?

Ben: Oh, because you guys are nicer, you don't want to talk about hard stuff?

Lee: Yeah. Yeah.

Ben: I don't know. I haven't really given that much thought, but when you talk about love, what comes to me and what's been inspiring to me is a quote from Cornel West, who said that justice is what love looks like in public.

Lee: In public. Yep. Yep. Yep. That's a pretty great line, yeah.

Ben: That's where it's at. I mean, that, that's where I'm coming from. I mean, if I'm not helping to create justice for people that are being abused by the police, I am not loving those people.

And what I need to point out is that, the huge majority of cops, are doing a great job, personally, but allcops have taken an oath to hold themselves and their fellow cops accountable.

And the other reality is that the majority of cops do not hold other cops accountable. There is the blue wall of silence. I think that there is a culture in policing, that you have a good cop coming into the field and they are told and shown in no uncertain words in no uncertain terms by the other cops, that if you go and report wrongdoing on the part of some other officer, you will be shunned. So there is that deep dysfunction in the system that needs to end. And the way to do it is to hold cops accountable, hold them accountable for the oath that every one of them has taken.

Lee: So allow me, if I can to kind of jump back earlier in your career, you and Jerry published a book entitled Ben & Jerry's Double-Dip: How to Run a Values Led Business and Make Money, Too, which I will say it has quite a few laugh out loud moments. It's well done. Early in your career, college experience was not so great for you?

Ben: Yeah. I’m not a real good, uh, classroom learner.

That, that, that is not my preferred learning style. So yeah.

Lee: So advice for college professors?

Ben: Advice for college professors? Well, college professors should continue to profess. I think that, I think they should understand that the job is kind of about performance and that they need to, you know, present in ways that are, interesting.

And, well, just interesting, and engaging.

Lee: Yeah. That's fascinating because I think that I finally learned that lesson after I started putting on a variety show and I, and I, I realized how much better one can teach by thinking of the classroom experience as their performance. So yeah, that's, very helpful feedback.

One of the things that's fascinating to me is that you and Jerry seemed to have been intentional about holding the playful along with the social witness. So reading your story about your fall festival, that when you started out early in Burlington, you and your alter identity, the noted mystic “Habeney Abdul Ben Coheney”

Ben: Yeah. Yeah. You know, Jerry, uh, went to Oberlin. And he went through four years straight at Oberlin College and, they set up this experimental college while he was there, where the courses were taught by students. And, he took a course in carnivals technique.

And he learned how to smash a cinder block on somebody's stomach with a sledgehammer while they were suspended between two chairs and, you know, so he came out of that course with flying colors. He said, let's do this act. Do you want to be the guy with the sledgehammer or the guy with the cinder block?

And I was not confident enough in my aim. So I said, I'll be the guy with the cinder block and, yeah, he's going around. So the Habeney Abdul Ben Coheney part of the gig, the act, is that I am presented as Habeney Abdul Ben Coheney, the noted Indian mystic, who was able to survive the destruction of the temple at Rishikesh by placing himself into a metabolic trance as the temple crumbled down about him. And I would simulate that for you here today.

Lee: No accidents?

Ben: No.

Lee: Have you thought much systematically about how holding the playful and the serious works together?

Ben: I think that, you know, there's a quote up on the wall of my office that says if I can't dance, I don't want to be part of your revolution. Uh that's from Emma Goldman. So, yes, it's got to be fun. It's got to be enjoyable. The joyful journey for justice. I mean, if it is all doom and gloom and a slog and no fun and serious who the hell wants to do it?

Lee: You're listening to Tokens: public theology, human flourishing, and the good life. We’re most grateful to have you joining us.

If you've not yet done so, subscribe today to the Tokens podcast on Apple, Spotify, Stitcher, or wherever you get your favorite podcasts.

Lots of great feedback about our recent episode with Professor Krisin Neff on her work on self-compassion: thanks to Marisa Whitsett Baker, Jessica Buckley McCoy, Mark Harris, Shane Moe and so many others for chiming in on social media about that episode. Thanks too for the kind words from David Schnelly, listening on his drives between Atlanta and Tampa, and for his gracious feedback about the episode entitled "Good Trouble" with Matt Maher, Leigh Nash, and Ruby Amanfu. And Robert Brady recently writing in with an outstanding list of potential interviewees. We do love hearing from you all, and are always pleased to hear some of the things you'd like to hear more about. You can email us at podcast@tokensshow.com.

Also remember you can sign up for our email list, or find out how to join us for a live event, all at tokensshow.com.

This is our interview with Ben Cohen of world-famous Ben & Jerry's Ice Cream, for which I did a fair amount of experiential research, tasting various ice creams flavors. Currently my two favorites are the Cookie Dough; oh, goodness; and the Tonight Dough, with the picture of Jimmy Fallon on the front. Oh me. Coming up, we'll hear more about Ben's ways of doing business and justice in tandem, as well as how the U.S. might benefit from his principles on using ones resources for peace rather than mere personal gain.

Part two in just a moment.

HALFWAY POINT

Lee: Welcome back to Tokens and our interview with Ben Cohen.

So y'all started out your business. You decide your business wants to be different, and you began with a model of simply giving away some of your profits.

And yet then I don't know if it was slowly or rather rapidly, you move into a more expansive model for what it means to be doing the kind of business you want to do.

So could you kind of describe the way that vision expands?

Ben: Sure. And it was slow. When we first got into business, we felt like business was essentially a machine for making money. And if we wanted to be of as much benefit to the community as possible, we needed to give away as much money as possible.

And we were giving away seven and a half percent of our pre-tax profits, which has the highest amount of any publicly held corporation.

Lee: And I think the average at the time was something like one and a half percent.

Ben: Correct.

Lee: Yeah.

Ben: And we realized that, you know, we were making all these grants, but, it was really just a drop in the bucket.

I mean that the needs, of the society are so huge that giving away, you know, a few hundred thousand or a few million a year, isn't really going to solve the problems.

And so we started looking at, you know, how else could we work on these issues. And we realized that if we could figure out a way to integrate social concerns into our day-to-day business activities, that would be way, way more powerful. And it is. And so in terms of how we buy our ingredients, it's fair traded and we're supporting, organizations that, there's one called the Greyston Bakery in Yonkers, New York that, uh, it's a bakery that was actually started by a religious organization. And, they have this commercial bakery and we deliberately decided to source our brownies for our Chocolate Fudge Brownie ice cream from them, in order to help them with their mission, which is to provide employment opportunities for formerly unemployable people. Ex-convicts ex-drug addicts, people living in poverty. So the more we can integrate social concerns into our day to day activities. It's not dependent on generosity or donations. It's just how we do business and it doesn't cost us any money.

We have a bunch of scoop shops that are operated by nonprofit, social service organizations that are working with at-risk youth.

And then the other thing that we realized is that probably business's most powerful tool is its voice. That when business speaks, the press listens the politicians listen, the community listens. And so we've been trying to use that voice, for justice.

Lee: So you said the process was slow. What were your practices or habits or, the process like through which you came to see different elements that you could then begin naturally building into your venture?

Ben: Well, the goal was to integrate social concerns into as many of our day-to-day business activities as possible.

And really what we used as the impetus for that was to change the way that we measured the success of our business. You know, normally businesses just measuring its success by profit. How much money is left over at the end of each month. And, we said that we were going to change that and develop a two-part bottom line, which is how much have we helped to improve the quality of life in the community and how much profit have we made?

At the beginning it was quite controversial at the company and people thought that, you know, trying to help the community was gonna take away from profits. And the focus on profits was going to take away from helping the community. And we found that we were able to find ways of choosing courses of action that had a positive impact on both parts of the bottom line.

Lee: One of my former students last night sent a note saying Ben & Jerry’s kept CEO pay linked at seven times of their lowest wage workers before selling. This comes from a former student, Benji Jones, who actually now works for one of the largest well-known corporations in the world.

And he said, that you all kept it linked at seven times, their lowest wage workers before selling.

And then I saw some other kind of research that indicated the American average these days is something like 350 times the lowest wage worker, as high as 1500 times. And he asked what does Ben think is a reasonable, maximum wage for the U.S.A.

Ben: Hmm. I haven't thought about what a reasonable maximum wage is. You know, at the time when we instituted our, compressed salary ratio. The norm you know, spread, between CEO and line worker pay was forty to one. And we thought that was outrageous. Now it's 10 times that, so, you know, CEOs currently are getting paid, what hundreds of millions of dollars, probably more. Nobody needs that much money. It's absurd. I mean, when we think about probably the biggest problem in our society is the increasing spread in wealth between rich and poor, that’s a big thing that's driving it.

Lee: Yeah. Right, right. Well, another, another thing that you've been getting quite a bit of talk about in the public media recent opinion piece in the New York Times about Ben and Jerry stopping sales in the Palestinian territories in an attempt to underscore the injustice of Israeli settlements. And of course, this is, fascinating because you're a Jew. And so talk to us about how y'all came to think about this and making such a statement or you supporting Ben and Jerry corporation making such a move.

Ben: Yeah, I'm a Jew. I'm also an American and I've criticized many actions of the American government. I'm still an American, and, uh, I consider myself to be a patriot and, I'm a Jew and I'm criticizing an action of Israel. And I'm huge supporter of Israel as a state that should exist as a homeland for Jews.

But I think they're really in the wrong in this instance. I think it's absurd to think that you can achieve security by impoverishing, you know, what, millions of people, and, keeping unemployment at north of 40% abusing people's human rights. That's a breeding ground for terrorists.

And, so just in terms of justice and human rights, yeah, I believe that Israel is wrong. And, and in terms of even self-preservation of Israel, I think they’re wrong.

Lee: You refer to yourself as a patriot. And I wonder if you have any commentary on why you think the notion of patriotism seems to have skewed toward non-critique of the government or the land one loves?

Ben: Yeah. Why is it patriotic not to criticize your government? I don't know. But I do remember very strongly learning in elementary school that, I think it was Patrick Henry who said, my country, may she ever be right, but my country right or wrong. I don't agree with that. I, I think if our country is doing something wrong, the patriotic thing to do is to try to get our country to change that.

Lee: Yeah. You have, in one radio episode, I heard you, um, cite Jesus. One, do you do that often? And two looking at yourself, what do you make of your citing Jesus?

Ben: I love Jesus. I mean the guy is about love and peace and taking care of people that are oppressed.What's not to love about Jesus. Jesus.

Lee: I know early on I think maybe, I don't know if Jerry pushed back at you or other people in the company pushed back at you about your Peace Pop, and the attempts to raise attention for the 1% for peace campaign. And I noted that you currently today, are affiliated with at Drop the Mic which is similarly doing critiques of the military industrial complex. Drop the Mic says in its kind of description at Twitter, the military industrial complex is killing us. It sucks money from what we really need in order to build an arsenal capable of destroying the entire world. And so this seems to be a concern that you've had throughout your career from early on and still now.

But talk to us a little bit about that. What are your concerns and what are the things that you really wish people would pay more attention to in that regard?

Ben: Well, I mean, in terms of the stuff that people really need, education, healthcare, housing, just money to go out and have a good time. It's all being sucked up by the military industrial complex. What Americans need to realize is that it is America that is leading the arms race. You know, you read the newspaper and it says, oh my God, China is building some new weapons system. We need to spend more to catch up. You know, Russia is building some new thing. Oh, they're getting militarized. I mean, the reality is that those countries are spending one sixth of what the U.S. spends, or one 12th.

They're trying to catch up with us. They're scared that the U.S. is the only country that, uh, has the capability of blowing up the entire world many times over. What smaller countries have learned is that if you want to keep the U.S. from invading you, you need to have nuclear weapons and then they'll be scared of you, then they won't screw around with you. If you survey the people around the world, which country is the rogue nation? I mean, it's the U.S.

So, you know, if you look at our discretionary budget, that's the amount of money that Congress has available each year to spend.

Over 50% of it goes to the Pentagon, we can't conceive of the magnitude of the amount of money that's going into the Pentagon. It's over $2 billion a day. For 15% of the Pentagon budget, we could provide food for all the people around the country, around the world, including our own country, that don't have enough food. We can provide healthcare for all the people around the world that don't have enough healthcare.

We have gobs and gobs and gobs of money. We're just spending it in the wrong places. I mean, do we really think that some country wants to invade the United States?

Think about this. The United States is the most powerful military force in the world, and we're not able to occupy Iraq or Afghanistan.

Some other country is going to try and occupy us? Ain't going to happen.

Lee: Going back to what you said earlier, I'm an American, but I can critique America.

I'm a Jew and I support the state of Israel, but I can critique the state of Israel. One of the things that I appreciate as well about Drop the Mic is that it's fairly nonpartisan in its critiques as well. You know, I saw plenty of critiques of Obama and Biden along the way as well when you see certain things.

Ben: Well, I mean, the horrible thing about the way politics works well, one of the horrible things about the way politics works in the U.S. is that, you know, the Democratic party and the Republican party when there's an election, they try to outbid each other in terms of how much am I going to spend on the Pentagon. Both parties have spent unconscionable amounts of money on the Pentagon. And I think essentially the reason why that happens is that, somehow the public has gotten convinced that spending more money on the Pentagon makes us more secure. And nothing could be further from the truth, but, trying to figure out, you know, all this military stuff and our military versus other people's military, you know, is very, very complex. So the shorthand becomes well, if you spend more money, you're stronger and more secure.

If you spend less, you're weak on defense. And that criticism of being weak on defense is politically, very damaged.

Lee: Yeah. One closing question. When you think back about your career, could you identify a significant mistake or two or habit that was unhelpful to you? And then a helpful habit or disposition that was helpful to you along the way?

Ben: Well, I think that, when I was a young man, a young manager at my company, I was very focused on perfection and continuous improvement, always working to do things better, always finding a way to try to make the product better, to make working processes better, whatever.

And I thought that people that I hired that was their job was to do things perfectly. And, uh, you know, if they did things perfectly, I didn't see any reason to praise them because they're just doing their job. That's what I'm paying them to do.

And if they did things imperfectly, I saw a lot of reasons to criticize. And I learned that one point. I, you know, things were not going that well. It’s not a good way to work with people. And luckily I had a partner Jerry, and you know, so I’d go around the office, walking around different stations and say, that's not right. That's not right. And you're not doing that right. You're not doing that right. And, and he'd go around behind me and he'd say, well, what Ben meant to say was. He'd put it in more diplomatic terms.

And what I learned, what really struck me, at one point I read an article saying that working with people is like a bank account, that you can't take money out before you put money in. And when you compliment somebody on the job they're doing, you're putting money in and when you criticize them, you're taking money out.

And you cannot take money out before you put money in. And that was a revelation for me, and it really sunk in. And, I think there was another business book written at some time called Catch People Doing Something Right. And, that sunk in too. And learning to work to people's strengths, to recognize their strengths and focus on that has really helped me quite a bit.

Lee: Was there a particular habit or virtue you had going into this that you think has helped you to do well? Something that you've been able to look back and think, yeah, that's something that was therehas really helped me do what I've done?

Ben: I love to learn new stuff and that has helped me. I like to constantly find ways to improve. That's also really helped.

Lee: Well I would assume that that desire for improvement has played a lot into the social activism as well. Well, this has been a delight. Thanks so much for your time. Appreciate very much your, your work in the world.

Ben: Great talking to you, Lee. I really appreciate you letting me know you were here in Vermont. I'm glad that we're having this conversation. You're you're kind of a fun guy to hang out with. We should do this more often.

Like I said, I'm going to be in Nashville.

Lee: Excellent. Well, I look forward to that.

We've been talking to Ben Cohen here at his office in Burlington, Vermont, founder of Ben & Jerry’s. Most recently the author of a new book entitled Above the Law: How “Qualified Immunity” Protects Violent Police, and also the author along with Jerry Greenfield of Ben & Jerry's Double-Dip: How to Run a Values Led Business and Make Money, Too. Thanks.

Ben: You bet.

Lee Camp: You've been listening to Tokens: public theology, human flourishing, the good life.

If you would like to hear more about business and social change, then you'll also want to check out our episode coming out soon with Jay Jakub, Chief Advocacy Officer for the Economics of Mutuality organization located in Geneva, Switzerland.

If you'd like to hear more about policing in America, you may find compelling and troubling our episode with Andrew Collins and Jameel McGee.

Remember you can subscribe to our podcast on Apple podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, or wherever you get your favorite podcasts.

Got feedback? We'd love to hear from you. Email us text or attach a voice memo, and send to the address podcast@tokensshow.com.

And give us a little love by going over to iTunes and giving us one of those glowing five star reviews.

Our thanks to all the stellar team that makes this podcast possible. Executive producer and manager, Christie Bragg of Bragg Management. Co-producer Jacob Lewis of Great Feeling Studios. Associate producers Ashley Bayne, Leslie Thompson, Tom Anderson, and Brad Perry. Engineer Cariad Harmon. Music beds by Zach and Maggie White, and Blue Dot Sessions.

Thanks for listening, and peace be unto thee.

The Tokens podcast is a production of Tokens Media, LLC and Great Feelings Studios.

LEARN MORE