“Things didn’t come together vocationally for me until I was 50.”

Now 84 years old, Quaker writer, speaker, and activist Parker Palmer has much to say about living a good life. And in his experience, a good life is often hard-won and counterintuitive.

In this episode, Parker covers a lot of ground, offering wisdom gleaned from a life lived at attention to the makings of a good life. He tells about his experience seeking and finding vocation, discovering how a rich life entails the embrace of paradox, and living through three major bouts of depression which gave him an increased attention to life’s small things.

Show Notes:

Similar episodes

Resources mentioned this episode

Subscribe to episodes: Apple | Spotify | Amazon | Stitcher | Google | YouTube

Follow Us: Instagram | Twitter | Facebook | YouTube

Follow Lee: Instagram | Twitter

Join our Email List: nosmallendeavor.com

Become a Member: Virtual Only | Standard | Premium

See Privacy Policy: Privacy Policy

Shop No Small Endeavor Merch: Scandalous Witness Course | Scandalous Witness Book | Joy & the Good Life Course

Amazon Affiliate Disclosure: Tokens Media, LLC is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

Transcript:

Lee Camp: [00:00:00] I'm Lee C. Camp, and this is No Small Endeavor, exploring what it means to live a good life.

Parker Palmer: Rabbi, rabbi, before I die, how can I become more like Moses?

Lee Camp: That's Quaker writer, speaker, and activist Parker J. Palmer. He's retelling a Hasidic tale about a man named Zusya.

Parker Palmer: And the great rabbi says, "when you get there, son, they will not ask you why were you weren't more like Moses. They will ask you why you weren't more like Zusya."

Lee Camp: At age 84, Parker is a man who has become himself as much as anyone I've ever met. Our conversation mines his vast experience and explores the meaning of vocation, the necessity for paradox in our lives, as well as some radical vulnerability about his own bouts with serious depression and the hard road of coming out the other side.

Our conversation, coming right up.[00:01:00]

I am Lee C. Camp. This is No Small Endeavor, exploring what it means to live a good life

In the first or second year of my being a professor, our provost invited the Quaker writer and activist Parker J. Palmer, to come lecture on one of his books entitled The Courage to Teach. That series of lectures would go on to inform my many own subsequent years of teaching college students. And it was one of those moments where one thinks, I wish I could have a long conversation with this human being, this fellow traveler who clearly has so much more wisdom than I do.

Which is precisely one of the things I love about hosting No Small Endeavor. It gives me a grand excuse to spend time with such fascinating human beings. So I asked Parker Palmer if I could travel up to Madison, Wisconsin [00:02:00] and spend the day with him and his wife, Sharon, and he said yes.

So today we're pleased to share our conversation with Parker J. Palmer.

Parker J. Palmer is a writer, speaker, and activist who focuses on issues in education, community, leadership, spirituality, and social change. He's the founder and senior partner emeritus of the Center for Courage and Renewal. He holds a PhD in sociology from the University of California at Berkeley.

He's the author of ten books, including several award-winning titles that have sold over two million copies, been translated into twelve languages. Dr. Palmer is a member of the Religious Society of Friends, and Dr. Palmer and his wife Sharon live in Madison, Wisconsin. And I'm delighted to be here in Madison at Dr. Palmer's home.

Welcome to No Small Endeavor, Parker.

Parker Palmer: Thank you, Lee. It's great to be with you.

Lee Camp: Well, I suppose if we're gonna have the opportunity to cover a lot of ground today with you and, um, so grateful for this time with you, but I su-- suppose I wanna start [00:03:00] first with your notion about vocation and, um, perhaps one of the reasons that the tagline for our show is 'exploring what it means to live a good life.'

And as I read your work on vocation, it seems crucial for you, in your life of seeking to live a good life, that coming to some sort of clarity about vocation for you was kind of, kind of a central practice for leaning into a good life.

And I wonder, here near, late in your life, and you think about your own pursuit of clarity or an understanding of vocation, what are some of the moments that you're so thankful for or that you have gratitude for with regard to clarity or pursuit of some understanding, at least, if it's not clarity about vocation?

Parker Palmer: Hmm. That's a great question. Age 84. You have a lot of moments to think back on, so I'll see if I can collect some of them quickly.

I think that my best [00:04:00] general answer to that question, Lee, is that I'm particularly grateful for the moments of challenge and difficulty, even for a sense of failure or a sense of being on the wrong track, because those are the moments that clarify things for you. Those are, those are the moments when you have an opportunity to do course correction.

I'm a big fan of the title that Gandhi gave to his autobiography, where he writes about his life as "my experiments with truth." And I think, I think life is a big experiment, and one of the experiments is around that sort of central question, why am I here?

Uh, which is, which is a complicated question because it's not only about, who am I? It's also about, whose am I? It, it's a question of selfhood, identity, and [00:05:00] integrity on the one hand, and it's a question of community on the other. Where am I planted? What ecosystem am I here to serve?

And I think it's important to say that vocation doesn't necessarily equal job, which is a common confusion I think.

It, it means purpose. It, it means, how are you making meaning in your life? Which is a pretty fundamental human need, to make meaning or find purpose. And for me, that's been a long series of experiments. It certainly has taken me on a very jagged, irregular course that one could not have imagined during, you know, one's senior year in high school or college when they had vocation day or, you know, what, what do you wanna do with your life?

That's an unfolding question, for me, that keeps appearing in different iterations at different times, uh, and [00:06:00] yields different answers. I, I think I was-- and I, I say this a lot to younger people who come to me looking for vocational guidance. I like to tell them that things didn't come together for me vocationally until I was 50.

Lee Camp: Mm.

Parker Palmer: Well, well past halfway through my life.

Lee Camp: Mm.

Parker Palmer: I finally got a sense of how all these meandering trails, which we can talk about later if you'd like, converged in, in some sense of coherence, at least in my mind, and in, and in my work. But until then, I was just doing my best to follow the track that seemed to be opening before me at the time, trying very hard not to press some, some design on it, but to just feel for the natural openings, that would take me a next step and a [00:07:00] next step.

Lee Camp: Mm.

Parker Palmer: Sometimes taking me to a dead end, at which point you back up and you find your way back to something that sort of makes sense.

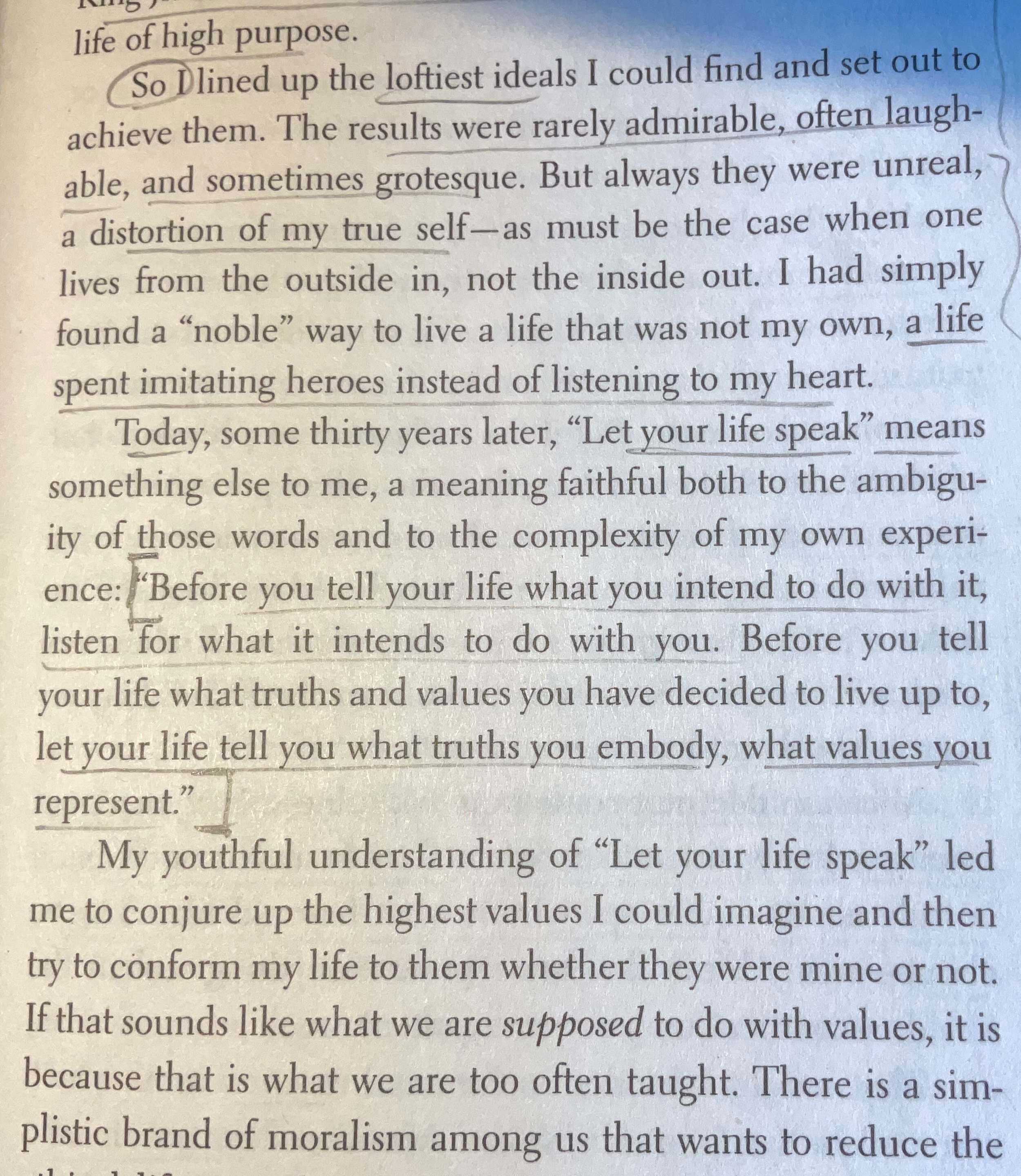

Lee Camp: On the notion of integrity that you pointed to, you, you suggest at one point, it's possible to live a life other than one's own.

And you share how you do a measure of that in lining up kind of lofty ideals for yourself, and then you discovered at some point that's, that's not really who I am. Would you kind of unpack that a bit for us?

Parker Palmer: Yeah. I think a lot of people are, are used to this notion and have struggled with this notion that early in life, we sort of do what important influential people in our lives wanted us to do or expected us to do. Parents, professors, mentors of various sorts, friends who, who wanted to see us be this or do that. [00:08:00] And, and eventually we have to find our way back to what it is that we're really called to do.

And we have voices inside of us that call us in a direction that isn't necessarily an imperative of the soul, but is coming from a different part of our own inner landscape.

I want to look noble. I want to emulate the heroes, my heroes, who did noble things. If one is not gifted to do those particular noble things, and no one is gifted to live someone else's life--

Lee Camp: Mm.

Parker Palmer: And Thomas Merton may be my hero, John Lewis may be my hero, but if I'm not gifted to do what they did, then I'm gonna make a mess of it. And the effort to be heroic is going to end up being both foolish and perhaps doing some [00:09:00] damage.

If you're not gifted to pursue a particular vision, you are li-- you likely will do some damage along the way. So finding out what vision is yours to pursue. Again, there's, there's this old Shaker song 'to come down in the place just right'...

Lee Camp: hmm.

Parker Palmer: ...in life is, is I think, an aspiration that you follow through attentiveness to the clues of your own experience. So you're conducting all of these experiments with your own truth. What are you learning? What's working? What isn't working? And then, follow that.

Lee Camp: You, several times you tell a story, a Hasidic tale, about, I don't know how you pronounce it... rabbi Zusya?

Parker Palmer: Zusya. Zusya. Mm-hmm.

Lee Camp: Yeah. Would you tell that story?

Parker Palmer: Yeah. So the, the story is from the collected tales of the Hasidim, which were collected I think by Martin Buber, about the disciple Zusya coming to the Great Rabbi and saying, "rabbi, [00:10:00] rabbi, before I die, how can I become more like Moses?" And the great rabbi says, "when you get there, son, they will not ask you why weren't, you weren't more like Moses. They will ask you why you weren't more like Zusya."

Um, and, and so, you know, there is a fundamental Christian belief that we are born in the image of God and that, that there is, as Quakers would say, I'm a Quaker, there is that of God in everyone. There's this kind of divine imprint that makes every human being of, of sacred worth.

To me that means we are stamped with a kind of selfhood. That it's important to try to discern the, the shape of that selfhood. To, to understand what this particular kernel is meant to grow into. That doesn't mean that anything is predetermined, because a kernel, just like a gene in our genome, [00:11:00] expresses itself differently in different contexts and situations.

So there's a lot of discovery to be doing, but there's, there's always this germ of identity and integrity. And if you pay attention, you know when you're off course. You're, you're uncomfortable. And sometimes, sometimes it's way beyond discomfort. It's into profound depression or despair, which I've known some of in my life.

There are all kinds of ways in which the human self asserts itself and insists on itself. You know, in our culture, we pathologize so much of this and we say, well, if you're depressed, pop a pill. That may be necessary for some people because some depressions are in fact based in brain chemistry and should be corrected. But, but so often depression also has a situational element, where we have [00:12:00] veered off course.

There are in fact evolutionary biologists who think that depression was an evolutionary adaptation to keep us from going too far off course. It's a very interesting theory to me because I've had this experience of wandering so far off course, and then depression hits, depriving you of energy or will to wander any farther off course, which is, which actually can help save your soul if you pay attention to it.

So, there is, there is this, I think, inexhaustible source of guidance within us, which certainly can be named True Self, something Thomas Merton wrote about a lot. Identity and integrity. It's, it's named many different ways in different traditions, but every wisdom tradition I know anything about has a way of naming that, that core of self that [00:13:00] constantly is, is saying, 'pay attention to me and figure out what this means in your current context.'

Lee Camp: Yeah.

So there are, there's some who are suggesting, like I'm thinking of one writer for example, who, who says follow your passion is terrible advice because if you sit around waiting until you feel passion, you'll never do the work that you've gotta do to become good in a given field.

How do you, how do you respond to that? What do you think about that?

Parker Palmer: Well, passion is an interesting word 'cause it also roots in suffering. It isn't, it isn't just joy. It, it's suffering as well. So I think hard work is a necessary component of any vocational path, no matter how you construe it.

Lee Camp: Mm-hmm.

Parker Palmer: Where, where it's coming from, how you understand it, and when I said a few minutes ago that one of my [00:14:00] biggest vocational clues was, 'I can't not do this,' with that, I can easily say, at the moment when I was making that decision to walk away from academia and become a community organizer in Washington, DC, I was not feeling incredibly excited and enthusiastic about all the vocational and financial risks that was going to entail for a guy who was married and by that time had two and then three kids. I just wasn't feeling like, boy, am I wild crazy to jump off a cliff and do this knowing that I, I would have a secure income as a professor, but not as a community organizer, where I knew going in that we would be raising our own salaries three months at a time from foundations, federal and local grants. So I have no trouble [00:15:00] saying, yeah, wild enthusiasm doesn't always come with, with this follow your heart or follow your identity and integrity.

Yeah, especially if you understand this is something you can't not do.

Lee Camp: Yeah.

Parker Palmer: Tha-- that doesn't go hand in hand with wild enthusiasm about risk taking, but risk taking is involved, anytime you get off the beaten path, risk taking is involved. And um, I think I was just built in such a way that, had I not taken that risk, I'd be sitting here today, I think, feeling pretty impoverished by the road not taken.

Lee Camp: Mm.

You're listening to No Small Endeavor and our conversation with Parker J. Palmer.

I love hearing from you. I really do. Tell us what you're reading, who you're paying attention to, or send us feedback about today's episode. You can reach me at lee@nosmallendeavor.com.

I've [00:16:00] been pleased in particular to hear from so many of you writing in about our interview with Rainn Wilson, as well as our interview with Martin Sheen.

You can get show notes for this episode in your podcast app or wherever you listen. These notes include links to resources mentioned in this episode and the PDF of my complete interview notes, which often includes material not found in the episode. And there you can also get a full transcript of the episode. I think for this particular episode, we've got some photographs there of my time with Parker Palmer.

Coming up, Parker and I discussed the need for paradox and the crucial importance of vulnerability in community.

Paradox has been another key recurring theme in your work, and you quote Niels Bohr several times.

Parker Palmer: Yeah.

Lee Camp: Can you share that with us and, and talk about how [00:17:00] paradox has been crucial for you?

Parker Palmer: Yeah, well, Niels Bohr was the Nobel Prize winning physicist. We all know him from physics class where we looked at the Bohr model of the atom, that you could sort of build out of Tinker Toys or something like that.

And Niels Bohr once said this very interesting thing. He said, "the opposite of an ordinary fact is a lie. But the opposite of one great truth may be another great truth." Now, it's important to note that he didn't say, the opposite of one great truth is another great truth. It may be another great truth. That's an act of discernment.

But I like that, I like that statement a lot, and I think it nails the heart of paradox for me, so that a paradox is understood as a 'both, and' statement rather than an 'either, or' statement. And in that sense, it kind of flies in the face of a lot of Western [00:18:00] logic. In Western logic, we're constantly talking about, it's either this or that.

Lee Camp: Mm-hmm.

Parker Palmer: We have this binary system on which computers are based, for example, it's a one or a zero. But in an alternative way of looking at the universe, which is more, I think, commonplace in Eastern than Western cultures, there's a lot of 'both, and.'

So I'll put, I'll put it to you this way. Are we made for community?

Absolutely, yes. Whether, whether you look at us biologically or theologically, we're made for community. We come from community. We're sustained by community. We're accountable to community. The community's fate and our fate are closely intertwined. We're made for community.

Are we made for solitude?

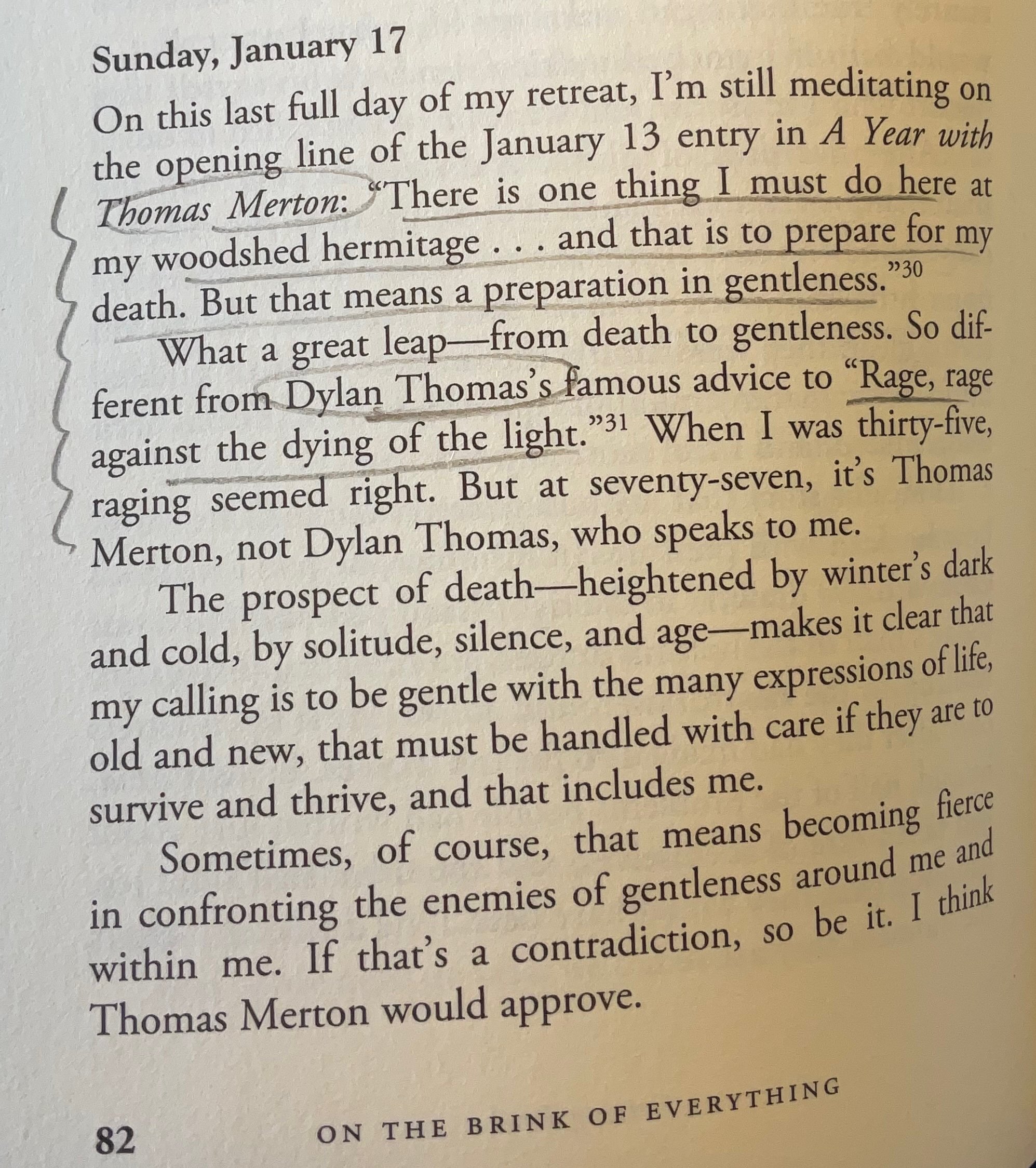

Absolutely, yes. There are parts of life, journeys in life that you can take only by yourself. No one can come along with you no matter [00:19:00] how helpful they want to be. I'm acutely aware of this, not only because I'm 84 and I'm looking at the passage of time where eventually I will, I will have to take a journey into dying that I can take only by myself. But I'm also, as you know, Lee, sitting here grieving a sister who died three weeks ago. And as much as I wanted to take that journey with her, holding hands, as it were, that could not be. She had to draw on all of her inner resources to take that journey alone. So the paradox is, we're made for solitude and we're made for community.

And if we try to split that, that paradox into choices, like, shall I go the communal route or shall I go the solitary route, we end up with a very unhealthy form of, of life. There's, there's [00:20:00] so much in life that, where we have to hold together the 'both, and' in order to be whole. And in fact 'both, and' is the form of wholeness. 'Either, or' is always a form of brokenness.

And, and so yeah, paradox has been huge for me.

This is why, for example, I look at education. I look at the kind of education that that focuses exclusively on cognition, on the operations of the human brain, as only half, at best, of an important paradox. Good education ought to be about all of the forms of intelligence that we hold in this 'both, and' reality that we live.

At very least, cognition and emotion. Cognition and feeling. Heart and brain. Only so, can, can we educate students to function [00:21:00] as whole human beings, rather than as thinking machines or just blobs of emotionality. We separate these things out, I think, and do damage to people and to the world that these people influence.

So when we get a politics, for example, that is infused with a lot of irrationality, that comes from the emotive side of life and is never clarified by an act of thinking, we're in real trouble.

Lee Camp: Mm-hmm.

Parker Palmer: And when we have a politics that is only calculated, analytic, pragmatic, strategic, we're also in trouble, because it, it eliminates feeling empathy for the human self and all of the selves that are impacted by politics.

Lee Camp: Mm-hmm.

Parker Palmer: So this is more than an abstract, philosophical concern for me. It's, it's [00:22:00] a, a lived issue, that we need to get better about.

Lee Camp: Mm-hmm.

One of the things that this invitation to embrace paradox does for me, is it puts me at a posture of curiosity. And it reminds me of one of my friends, a decade further along in teaching than me, when I first started as a rookie teacher I remember him telling me that he thought of one of the best things he did for his students was to give them better questions to ask.

Parker Palmer: Mm-hmm.

Lee Camp: And that, that deeply informed the way I then thought about my teaching was, if I can give my students better questions to ask that they can then take with them for years, I've done them a really helpful service, I think.

Parker Palmer: Mm-hmm.

Lee Camp: Um, but I think your, your emphasis on paradox similarly draws us into a sort of posture of curiosity rather than getting something nailed down.

Parker Palmer: Yeah, I appreciate that insight. I'm not sure I ever [00:23:00] made that connection in my own mind, but you're absolutely right. If you have an appreciation for paradox, you're always gonna ask in response to anything that's said to you, what's the other side of that?

Lee Camp: Mm-hmm.

Parker Palmer: And that's, that's the kind of curiosity that drives us forward. That's the kind of curiosity that asks the questions that otherwise don't get asked if you just settle for, you know, 50% of what's real or true.

Lee Camp: Yeah.

Parker Palmer: Yeah. So that's a nice connection. Thanks.

Lee Camp: Another element... when I was thinking back-- I, I told you when I reached out to you, that you came to my university, I think at the end or, of, end or start of my first or second year teaching, and, uh, were lecturing on Courage to Teach. And as I've reread back through Courage to Teach and was asking myself, what, what can I identify that that, that I, I remember resonating with so deeply? And a lot of it was the [00:24:00] emphasis that you give on seeing our teaching as an exercise in letting ourselves be known to our students.

How did you end up emphasizing this as such a significant element of the work of a teacher? Or the work of being human?

Parker Palmer: Yeah, I think, I think the answer to that is that this emphasis on, let me just call it being human in front of our students, as fully human as we're able to be, came for me in, in at least two ways.

One is, I started to realize, I'm revealing myself to them all the time, whether I intend to or not. My students aren't, aren't stupid. They're, they're constantly looking at what's behind the mask, what's behind the posture. And it won't hurt. It will probably help if I can, if I can open that, if I can take that mask off and open, you know, open [00:25:00] the posture a bit to give them more of what's really there, rather than leaving it to their imaginings.

It's always better to just know what's there than not. Among other things, when you don't know what's there, it's scary.

Lee Camp: Mm.

Parker Palmer: Is this guy gonna leap out from behind the mask and bite my head off?

Lee Camp: Mm.

Parker Palmer: You know? So that's one very basic reason. Doesn't much matter what I intend to do. I'm self-revelatory in every moment of my life.

Lee Camp: Yeah. Very helpful, very helpful. Touche, touche.

Parker Palmer: To anyone who's paying attention.

But the other reason is that this business of hiding the self in the act of teaching, or in the act of scholarship, seemed to me to be contributing to this mythos of objectivism, which intellectually has never made any sense to me at all.

Lee Camp: Hmm.

Parker Palmer: This, this notion that, that, that we, we know best by distancing ourselves from objects of, from objects of [00:26:00] knowing, and maintaining a pristine, antiseptic distance so that those objects are, as it were, untainted by the touch of human hands. Well, there's no such thing as an object that is untainted by the touch of human hands.

The very process, the very movement of wanting to know the world impacts the world. Physicists have proven that, that as soon as you move into of field, of, of knowing, you're making a difference in that field. And the only reports that we'll ever get out of that field involve both what we observed and the presence of the observer.

Lee Camp: Mm.

Parker Palmer: So let's just, let's just get straight about that. Let's acknowledge that. And let's also acknowledge that the greatest science gets done, not at a great distance from the object, but through a really complex blend of data and logic and [00:27:00] intimacy. Not with an object, but with a subject of knowledge. A, a drawing close through a passion to know and understand the--

Objective knowledge doesn't come from one person standing on Mars and looking at something on earth. Objective knowledge comes as various passionate observers of a phenomenon form a community of inquiry, following the same protocols, the same rules of evidence and rules of inquiry and analysis, and reach consensus on what it is they're seeing. It-- objectivity is the result of, of a lot of intersubjective exploration.

And any decent textbook on science will tell you that, that objectivity comes from intersubjectivity, which means people saying, yeah, [00:28:00] that's what I see too. And that's what I understand as I apply the protocols in a, in a faithful rendition of this discipline, whatever it may be. History, chemistry, literary analysis, whatever.

And, and so I wanted to, you know, I, I, I wanted to bust through that myth as best I could because it seemed to me that this myth of objectivism was rendering everything about teaching and learning distant and dull and unenlivening for, for anybody. And it was ramping up fear in the students, the fear that they, that they would get it wrong, because there's an objective standard for what's right.

Well, yes, there, there is. But it's temporary. It's what physicists have determined at this moment is the story of a quasar or another, [00:29:00] another subatomic particle. But if you look at what that story was in 1921, it's a different story than it is in 2023. And so I, I always ended up in, in my lectures on the courage to teach, saying, If you want to teach your students to be in the community of truth, to be in the community of seekers of truth, which I think ought to be our goal for all of our students, it's not enough to teach them the conclusions of the moment and say, if you can memorize this stuff and pass the test, then you, you get you, you get a credential from this institution.

Instead, you want to teach them how to be in the community of inquiry, how to be in the community of truth. And that involves all kinds of, all kinds of skills that have to do with cognition, that have to do with emotion, that have to do with relational capacities. [00:30:00]

Our knowledge, for example, in a variety of fields, has changed as membership in these disciplinary communities of truth have changed. So as more women have joined the sciences or any of the disciplines, as more people of color have joined any of the disciplines, as more people of diverse sexual orientation and identity have joined these communities of inquiry, our knowledge has shifted.

Sometimes subtly, sometimes dramatically. You, but you look at any history of of the United States of America that was written before Black scholars took on the work of writing American history, and you're looking at a fairytale that never existed.

Lee Camp: Mm-hmm.

Parker Palmer: Today, you're looking at a lot more truth and obviously that truth is challenging a lot of people who don't want [00:31:00] that kind of history taught.

But that's what it means for our students to join in an inquiry. It's not just about knowing how to be a historian, it's knowing, it's about knowing how to be a historian in a diverse company of historians. So the relational skills are just as important as the cognitive and-- skills and the emotional intelligence.

Lee Camp: Mm-hmm.

Parker Palmer: Yeah. So I, I think that all loops back to why it is that I have to show up as a real human being in my classroom.

Lee Camp: Mm.

We're going to take a short break, but coming right up, Parker is vulnerable about his several experiences with serious depression. He tells his story about the hard road to get through those times in a way that I found immensely helpful. Perhaps you will as well.[00:32:00]

You mentioned earlier your experience with depression, and you've written about this at some length. I was wondering if we could talk about that a bit?

Parker Palmer: Sure.

Lee Camp: You say, several places, "I'm not writing a prescription. I'm simply telling my story." Why, why is that important to you to say that?

Parker Palmer: It's important because depression comes in so many shapes and forms and from so many causes, and despite all of the science devoted to it, I think it is still not well understood.

At very least we know that some depressions have genetic causation, some depressions have biochemical causation, brain chemistry, and some depressions have situational causation. And a lot of depressions are mixes of the preceding three. [00:33:00] Um, very hard to untangle those threads and to say what it is that dominates or, or what it is that needs to be treated in, in a given instance.

There are psychiatrists who will say, if you can sweat it out, most depressions will just resolve themselves. There are others who say, yeah, but the risk of suicidal ideation or suicidal behavior is so great that we need to prop people up with antidepressants in order to get them through to the point where the depression might go away, they might become more functional again.

There are some people who need to be on medication for the rest of their lives, and there are some people like me, who have the good fortune to be able to be on medication for a while to kind of put a stable floor under their lives, but then are able to wean themselves off with [00:34:00] the help of a doctor, off of those medications and go back to, to living medication free.

There's just-- I never wanna talk about depression in a way that makes anybody think, okay, that's that's the way I've gotta do it too. I don't know how you want to do it if you find yourself in that situation.

Lee Camp: Yeah.

When you think of your own experience, I think you said you went through at least maybe two seasons?

Parker Palmer: Three, really.

Lee Camp: Three?

Parker Palmer: Yeah.

Lee Camp: When you've been in those seasons, what are ways that you might try to get at describing what that's like, or metaphors for des-- getting at what it's like, to whatever degree you might be able?

Parker Palmer: So my, one of my first metaphors for depression, and I wrote a little bit about it this way, was 'lost in the dark,' and later on it occurred to me that in its depths, depression [00:35:00] is not like being lost in the dark. Depression is like having become the dark.

Lee Camp: Mm.

Parker Palmer: And that's a significantly different metaphor.

If you're lost in the dark, there's still a distinction between you and the darkness, which means you can negotiate something with this other called the darkness or depression. You may not be able to see what's in the room, but you can, you know you're in a room, and you can feel around, maybe find a window or a shade to pull up, or a light switch or a door to open, or, you know, something that that would suggest a way out or a way forward.

You can do something if you're lost in the dark in a room. But if you've become the dark, there's no distinction between you and the depression. You are it. It [00:36:00] is you. And at the depths, for me, that's how it felt.

There is no reality in this world other than this darkness that I've become. And it's a sense of utter and absolute isolation. It's a sense of having, if you can even put it this way, at the time, and I probably couldn't have, but imagine losing your membership in the human community while you're still alive. In every bit of the human community.

So you're, you're just, you're alone on, on the surface of Mars. And it's, and it's an absolutely devastating feeling. Your capacity to connect with the human community, on which we are all so dependent, has absolutely disappeared.

And so people will ask me, well, you know, did faith, did religious faith help you [00:37:00] through those hard times? No way. That, that disappeared too. Religious faith is some kind of conversation or negotiation with the cosmos, you know, that often with other, with a community of people or an institution around that community. Nothing of that is present when you've become the dark.

Anything that could connect you to the human commu-- community would be a, would be not just a blessing. It would, might-- it might save your life.

But such moments are are not in, in your control. And when people say, well, how did you find your way through? All I've ever been able to say is, damned if I know. I, I just don't know.

But I flipped the question over in an important way for me. When I [00:38:00] wrote this, I thought, I'm probably gonna get in trouble for saying this, but I'm gonna say it anyway 'cause it's true, for me. Turns out I got a lot of gratitude for having written this.

Here's what I wrote: "People walk around saying, 'I don't understand why so and so committed suicide. Well, I understand why they did, 'cause I've been there and was tempted to do that. They did it because they needed the rest. Depression is absolutely exhausting. Drains the body of every bit of energy and will."

What I don't understand, if you want a question to wonder about, what I don't understand is why some people not only survive depression, but thrive on the other side. And I'm not satisfied with any of the answers I heard.

I mean, you could say sheer doggedness, you know, cussedness. Just, you know, the willingness to put one foot in front of the other. [00:39:00] Well, there was no willingness in me. There was no putting one foot in front of the other. Got a lot of help from a therapist who, with whom I met as I began to come out of the depth of the experience, 'cause until then I wasn't ready for, for therapy.

But this fellow talked to me about keeping a daily journal of what he called small successes. And I said, look, I'm not having any success at all. I'm unable to write, I'm unable to travel and speak. I'm just down and out.

And he said, well, let me explain what I mean. He said, I want you to just keep a journal at your bedside, and if you were able to get up this morning at 10:30, because part of the depression thing is you spend a lot of time in bed just with the covers over your head, hoping [00:40:00] that the world has gone away, if you're able to get up at 10:30 this morning, mark that down in your journal. The next morning, if you're able to get up at 10:15, mark that down and note it as a sign of success. If today you're able to ride your bike for 15 minutes and tomorrow you're able to ride it for 20 minutes, write that down. Note it as a small success.

He said, if you will do this faithfully, you will find that what feels like flatlining is actually getting a little better and a little better and a little better, but the increments of betterment are so small that you can't notice them unless you keep track of them.

And so I did that over a period of weeks and a couple of months, and he was right. It helped. It helped a lot. And it became an encouragement to me to be, actually be able to see some improvement. And then maybe even to, at [00:41:00] some point when I was, as I started getting some energy back, to challenge myself. Okay, ride your bike for 30 minutes today instead of 20 and, and see where that might take you tomorrow.

Lee Camp: Hmm.

Parker Palmer: But life gets measured in those small increments when you're in a state of depression.

Lee Camp: Right.

Parker Palmer: And that was a very powerful experience for me, because up to that point in my life, I had been looking for the big wins. You know, let's write another book. Let's write a book that gets good reviews. Let's write a book that gets you a lot of speaking invitations, with good fees attached. Big successes.

That wasn't happening anymore, and so I, I lost this calculus by which to measure my life.

Lee Camp: Mm-hmm.

Parker Palmer: The small successes that this therapist invited me to pay attention to, [00:42:00] I do that to this day. Um, I'm 84 and I'm not doing some of the big things I used to do, and if I were still dependent on those as a, as a calculus for my life, I might be in despair. But these days, I'm just grateful for all kinds of small successes. As that, as that sun sets, I feel my own collaborating with it in a graceful way.

Lee Camp: If you or someone you love is struggling with mental health, help is available. You can speak with someone today by calling the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, by dialing or texting 988.

As we, as we get close to our, the close of our time, I wonder-- I, I have on my outline here the question, 'regrets?' But I think that's tricky [00:43:00] territory to ask that kind of question, given all-- that very quote we just had, right?

Parker Palmer: Mm-hmm.

Lee Camp: Is that there comes a point at which all of the things, at some point in our lives we might say we regret, become indispensable fodder for who we've become.

Parker Palmer: Yeah.

Lee Camp: From, hopefully from which we've learned a lot about how to live life. But nonetheless, lemme just throw that out there. Regrets?

Parker Palmer: Well, I feel like breaking into song at this point.

Regrets, I've had a few.

[Both laugh]

Go the Frank Sinatra route, you know.

But no, it's, it's not, it's no longer a viable word for me.

Lee Camp: Yeah.

Parker Palmer: I think there, there are times when I've had regrets, when I did something stupid, when I did something embarrassing. And I've certainly done a few of those in my time. But in the, in the long run, in the great mix and wash of life, I can't think of anything where I messed up that didn't have, [00:44:00] that didn't play an important role in helping me to get it, if not right, at least a little more right next time around and next time around.

If you live long enough, you have a chance to keep going around, and so maybe it's longevity as much as anything that has allowed me to say, "no regrets."

No, you certainly regret the times when, when you hurt people, but if you work on reconciliation, if you work on forgiveness, even, even that, even those things can be redeemed.

One of my favorite poems in recent years is, is a poem called, um, 'Thanks, Robert Frost,' by a guy named David Ray. And I can't recite the whole poem to you, but it turns out that Frost, in his old age, had had been asked, do you have hope for the future?

And Robert Frost said, oh yes, I even have hope for the past.

[Both laugh]

[00:45:00] That, that it will turn out to have been better than we thought it was. And that even the heavy burdens we imposed upon our children's lives will turn out to be, you know, fruitful and liberating for them and for us. I'm very touched by that poem because it came to me at a time when I was already feeling, I have hope for the past too.

And, and that it... and, and I think it's a really important point that we always have a story about our lives that we carry with us and sometimes tell to other people, but even if we don't tell others, we're telling our it to ourselves constantly and it's shaping us as we go.

And it's not that you wanna lie about your life, not at all. But there are so many ways any story can be told. There's-- and, and you can take that moment of shame or humiliation and you can see how you, how it helped you grow.

Lee Camp: Yeah.

Parker Palmer: And if it hasn't helped you grow yet, then [00:46:00] now is the chance for you to do some growing. And, and I, so I'm much, I'm fascinated with the stories people tell themselves about their lives.

And I'm glad at this point to tell a story that isn't riddled with regrets.

Lee Camp: Mm-hmm.

Parker Palmer: But that is certainly full of learning, which was necessary for me.

Lee Camp: Yeah.

I've been talking to Parker Palmer at his home in Madison, Wisconsin. I'm so grateful for your and Sharon's hospitality today and your generosity with your, uh, time and yourself today.

And moreover, for your many decades of good work in the world. It's beautiful and compelling, and I thank you.

Parker Palmer: Well, thank you, Lee. It's been a great pleasure to be with you, and thank you for your generosity and wanting to hear the story. Greatly appreciated.

Lee Camp: Thank you.[00:47:00]

You've been listening to No Small Endeavor and our interview with Parker J. Palmer.

We gratefully acknowledge the support of Lilly Endowment Incorporated, a private philanthropic foundation supporting the causes of community development, education, and religion, and the support of the John Templeton Foundation, whose vision is to become a global catalyst for discoveries that contribute to human flourishing.

All right. Thanks to all the stellar team that makes this show possible. Christie Bragg, Jakob Lewis, Sophie Byard, Tom Anderson, Kate Hays, Mary Eveleen Brown, Cariad Harmon, Jason Sheesley, Ellis Osburn, and Tim Lauer.

Thanks for listening and let's keep exploring what it means to live a good life, together[00:48:00]

No Small Endeavor is a production of PRX, Tokens Media, LLC, and Great Feeling Studios.