There is a great danger lurking about, this generalized disdain for tradition, habit, and ritual, because: it is increasingly understood, in various fields of study, that cultivating the proper habits and rituals yields a dis-proportionately significant flourishing effect in our lives.[1]

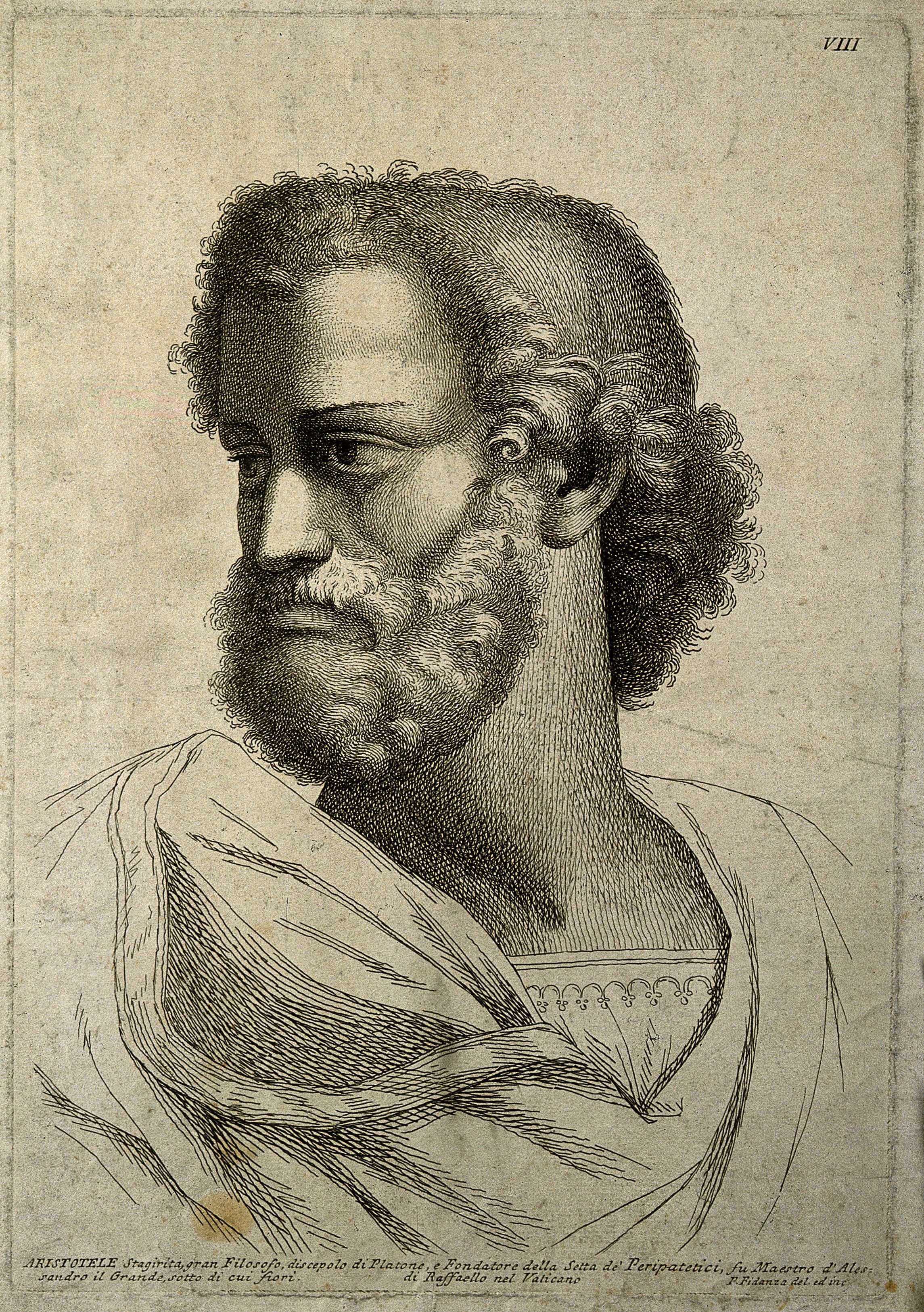

Such studies fascinate me, primarily because they resonate with an approach to ethics and theology I have found fruitful for a long time now: namely, various “virtue traditions” which have found their home among the likes of Aquinas and Augustine and Aristotle. These frameworks typically employs three primary constructs:[2]

First is the notion of an untutored, untrained self.

Second is the question of the end of life—end in the sense of purpose or goal. What does a good life look like?

And third is the notion of virtues—those habits or dispositions which best constitute a good life.

Note that the virtue traditions do not assume that we can simplistically “follow our hearts,” because our hearts may, in fact, long for destructive ends. Desires are (often? always?) good and beautiful. But the important question is whether they are rightly ordered toward life-giving ends.

Take for example my love of certain confections. Oh Lord, we give thanks (as one example) for dark-chocolate-covered-almonds-with-turbinado-sea-salt-from-Trader-Joe’s. A good source of protein! And dark chocolate is good for, well, something. These things are truly good, and good not merely in the sense of pleasure to my palate, but a good source of other good things, too.

But, I confess that a disordered, inordinate love of dark-chocolate-covered-almonds-with-turbinado-sea-salt-from-Trader-Joe’s often afflicts me. “Dad, where did all those dark chocolate almonds go? There was whole carton in here this morning…”

So our untutored, untrained desires lead to poor ends. Sex, friendship, food, security, and much more besides: all these things are indeed good. But it requires a good deal of training to do these things well, to enjoy them well. One will grow in proper enjoyment of these goods, or one will be mastered by them.

This whole notion then always begins with the question of the end. That is, what does a good life look like? In other words, I cannot necessarily say that the act of glutting myself with dark-chocolate-covered-almonds-with-turbinado-sea-salt-from-Trader-Joe’s is a bad thing, unless I have some sort of depiction of life that would allow me to judge otherwise. If one’s tradition is the Great Western Individualist tradition in which simplistically “following one’s heart” is the end-all-and-be-all, then it may be that the inordinate pursuit of dark-chocolate-covered-almonds-with-turbinado-sea-salt-from-Trader-Joe’s may not be all that bad.[3]

But there are a great number of traditions which see gluttony as problematic, and problematic for a host of reasons: as practical as the fact that my body feels badly afterwards, and my energy plummets after the sugar crash comes; as practical as the fact that those who exhibit no temperance in their enjoyment of pleasures soon find themselves unable to enjoy those things which once brought them pleasure; and as theological as the fact that such indulgence exhibits a sort of idolizing of food that is both symptom and symbol of a deeper bondage.

The ongoing conversation of what a good life looks like allows us then to be in conversation also about the question of means and constitutive practices. In other words, we ask what habits, skills, or dispositions help us attain or embody that sort of good life. As noted already, these habits and skills and dispositions are called “virtues.” On the contrary, habits or skills or dispositions which lead to all manner of bitter fruit in our lives—personally or socially—are called “vices.”

This is a much more fruitful way of teaching ethics than the surprisingly common yet exasperating method of presenting students with endless dilemmas.

You know, a typical case study like this: you go spelunking with a group of friends. On the way out, the fat friend tries to exit the cave first, and gets wedged into the hole, with no possibility for extraction; you and all your friends will die if you don’t get your friend out of the hole. There simply remains no chance of getting him out whole. Everyone is going to die of thirst. So, then, the stirring question for heated discussion among the students: do you, or do you not, use the three sticks of dynamite that you just happen to have in your backpack, to blow up the fat friend, and save everyone else?

This approach forces the conversation participants to choose between mutually exclusive principles, like: kill one to save the many, or never kill regardless of the consequences. Then, once that principle is selected, we are thought to have gotten clued into how we shall do our “ethics.” The dilemma forces the selection of a principle, which becomes the basis for our “ethics.”

Meanwhile, the much more interesting questions—what is a life for? what is economics for? what is friendship for?—and the like, never get raised. One can go through a whole semester of “ethics” and never be asked those questions. It’s exasperating, and a waste of good tuition dollars.

No doubt, dilemmas certainly arise in life. But Aristotle believed that one who was sufficiently schooled in the virtues would have the practical wisdom to assess all the relevant circumstances, and make a wise decision in the midst of the dilemma. One could not necessarily define ahead of time the right answer. Instead, one would be better off cultivating the habits of a good life. When dilemmas arise, one will then be equipped to deal with them.

This approach asks us to stay focused on the important questions about the overarching direction of one’s life, the overall purpose of life. And this approach asks also about the direction of human communities, and what makes for a good and shared common life.

So, this year in this series, “On the Cultivation of Habits for Living Life Well,” I will be reflecting upon these sorts of questions. I intend to take advantage of the blogging format to be altogether ad hoc, not keeping myself to any sort of systemic treatment of these questions. It will be more a sort of dispatches from the front of my own life. I’ll be reporting on things I either currently am or have in the past experimented with, and interesting conversations along the way…

{2018 Favorite}

Follow Lee on Instagram or Facebook.

Want to continue the conversation of habits for living life well?

Get the free PDF download: "How not to be a Sectarian" by entering your email here:

You may also like:

"25 Lessons (Re)Learned in 2017"

"Pride and Prison: A Dispatch from the Tennessee Prison for Women"

"Lee Guests on Ian Cron's 'Typology' Podcast"

Notes:

[1] See for example, The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business; You Are What You Love: The Spiritual Power of Habit; The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change, High Performance Habits: How Extraordinary People Become That Way

[2] Brad Kallenberg has a helpful overview here: “The Master Argument of MacIntyre’s After Virtue,” in Virtues and Practices in the Christian Tradition: Christian Ethics After MacIntyre, ed. Nancey Murphy, Brad J. Kallenberg, and Mark Thiessen Nation (Trinity Press International, 1997), pp. 7-29.

[3] Though even here, one can make the case that one can best enjoy such indulgences if one does it with temperance. The glutton and the lecher are auspiciously unhappy, unpleased and unpleasured people, quite unable truly to enjoy either chocolate or sex.