How do you reteach love to a community that society has deemed unloveable?

In the 80s and 90s, the city of Los Angeles was ravaged by what is now known as the "decade of death," a period of unprecedented gang violence, peaking at 1,000 killings in 1992 alone. It was in the midst of this unrest, fear, and finger-pointing that Father Greg Boyle became pastor of the poorest Catholic parish in the city, in order to live and work among gang members.

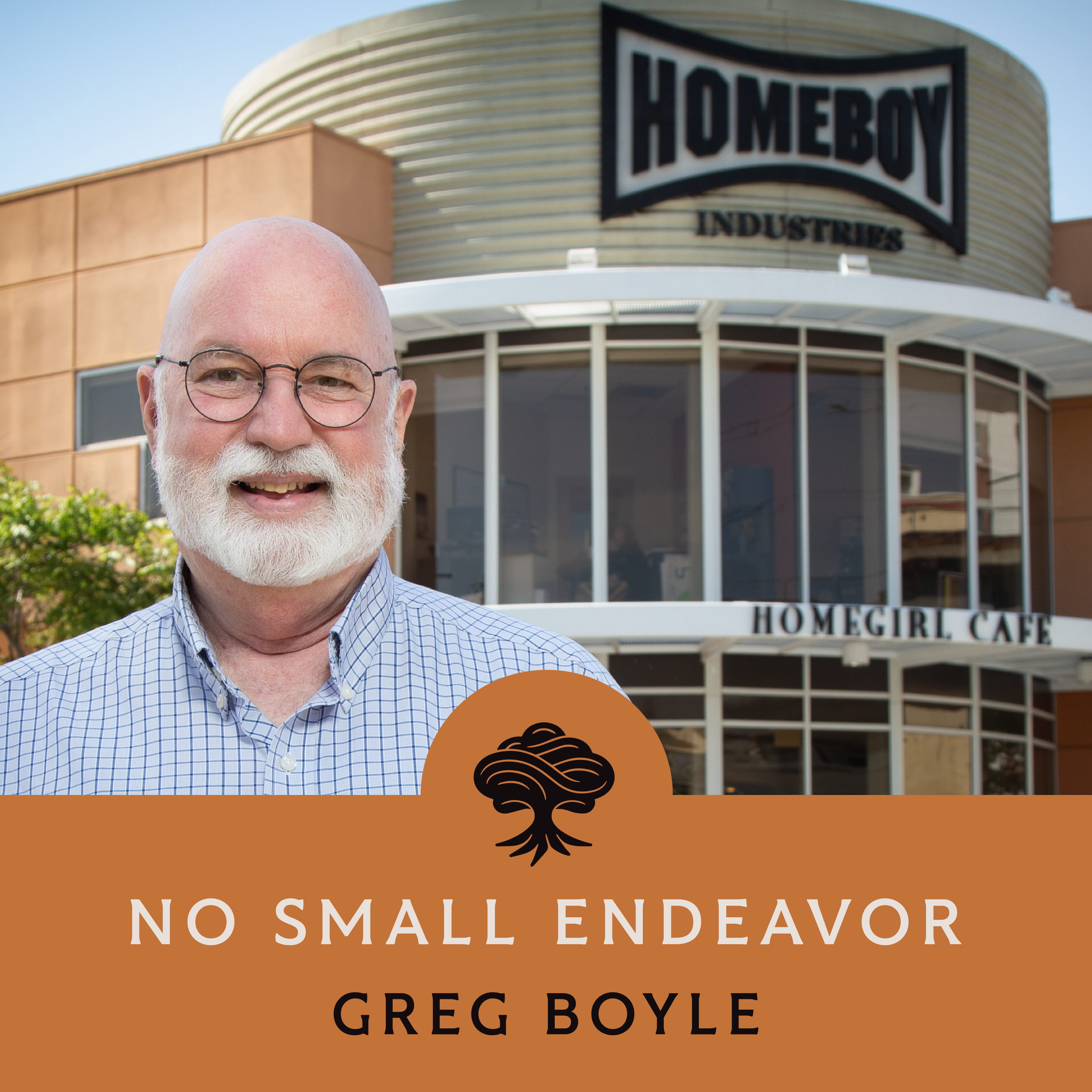

This eventually led him to start Homeboy Industries, which is now the largest gang-member rehabilitation and re-entry program in the world. In this episode, he tells some breathtaking stories, offering wisdom from a life lived in community with those who society neglects: “You don't go to the margins to make a difference. You go so the folks at the margins make you different.”

Show Notes:

Similar episodes

Resources mentioned this episode

Subscribe to episodes: Apple | Spotify | Amazon | Stitcher | Google | YouTube

Follow Us: Instagram | Twitter | Facebook | YouTube

Follow Lee: Instagram | Twitter

Join our Email List: nosmallendeavor.com

Become a Member: Virtual Only | Standard | Premium

See Privacy Policy: Privacy Policy

Shop No Small Endeavor Merch: Scandalous Witness Course | Scandalous Witness Book | Joy & the Good Life Course

Amazon Affiliate Disclosure: Tokens Media, LLC is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

Transcript:

Lee Camp: [00:00:00] One of the dangers, for me, of trying to be aware of what is going on in the world is the great weight of how much horrific or heavy news is always going on in the world. And in the midst of that, I must keep ready and close at hand exemplars of people who are doing good work in the world. And often I've gone back to my conversation with Father Greg Boyle.

You'll hear plenty about him in a second. But Greg exemplifies to me what I would call the good life paradox. In pursuing the question of 'what does it mean to live good life?' we've heard time and time again from guests that the good life is not and cannot be what we're often sold in America. It's not about being wealthy and accumulating as much as possible, it's not about fame or popularity, and it's not even [00:01:00] necessarily about comfort.

What is it about? I submit to you in this 'Best Of' episode with Father Greg Boyle that we're given one example of truly good life. Please enjoy. As always, you can reach me at Lee@nosmallendeavor.com.

I'm Lee C. Camp and this is No Small Endeavor - exploring what it means to live a good life.

Greg: You don't go to the margins to make a difference. You go to the margins so that the folks at the margins make you different.

Lee Camp: That's Greg Boyle, Catholic Priest in Los Angeles, California, and founder of Homeboy Industries, the world's largest gang member intervention program in the world.

One day, a former gang member entered Greg's office.

Greg: Big, huge hulk of a guy holds his hands in his face and just sobs. And he says, I have found my purpose here[00:02:00]

Lee Camp: Today, an episode full of the wisdom gleaned from a life of taking delight in the person in one's midst, and the gladness discovered in just showing up.

All coming right up.

I'm Lee C. Camp. This is No Small Endeavor - exploring what it means to live a good life.

Starting in the 1980s, the city of Los Angeles, California was ravaged by what is now known as the 'decade of death' - a period of unprecedented gang violence peaking at 1,000 killings in 1992 alone. It was a time of much unrest, fear, and finger pointing, turning many of the city's poorest areas into, for lack of a better word, war zones, desperate for socioeconomic stability and [00:03:00] communal peace.

And it was in the midst of this hostility that Father Gregory Boyle became pastor of Dolores Mission Church. At the time it was the poorest Catholic parish in LA, in the most violent neighborhood in the city.

Greg: I was pastor of the poorest parish in the city, as you mentioned. And uh, so that was 37 years ago that I first arrived. So, uh, the Homeboy is 33 years old. I was kind of working with gang members prior to that, but I was kind of forced to-- I mean, it wasn't, I never set out to do anything.

Lee Camp: 'Homeboy' refers to Homeboy Industries, a nonprofit organization Greg founded in 1988, which sought to address gang violence in a way unheard of at the time - to treat gang members as human beings.

Today, it's the largest gang member rehabilitation and reentry program in the world.

Greg: First thing we did was we started a school because we had so many middle school, junior high age [00:04:00] gang members who, no school wanted them. So once they got the boot, they were wreaking havoc in the projects and they were writing on the walls and violent and selling drugs.

So, so I went out to them and I'd say, "Hey, you know, if I found a, a school that would take you, would you go?" and, and they said, uh, "Yes."

But the main impetus was the fact that I was burying kids. So 1988 I buried my first, and on Saturday I buried my 249th. And then I, um, Thursday upcoming, I'll bury my 250th.

So, um, that was a, kind of a, a wake up call for us as a parish. [00:05:00] So we started a jobs program and, you know, and then started enterprises, you know, businesses, because we couldn't find enough felony-friendly employers.

Lee Camp: I take it from some of the stories you tell that it was not necessarily welcomed by all in the neighborhood when you started.

Greg: So the first ten years were death threats, bomb threats, hate mail - never from gang members, 'cause we always represented hope to them, but, you know, kind of fueled a lot by law enforcement.... Many of the anonymous letters were, 'I'm a police officer, I'm a sheriff, we hate you.' You know, 'you're part of the problem, you're not part of the solution.'

Which always seemed sort of confounding to me because it was abundantly clear to anybody close to the ground that if you, you know, invested in them or you engaged them in a positive [00:06:00] way, they weren't, uh, participating in anything negative.

And yet, they had so been demonized they were the enemy. So the friend of our enemy is our enemy. And so, that became untenable for folks. But, you know, the, the good news is, that's a memory that's hard to retrieve. So it's almost, you know, over-- it's been twenty years since that's been so pervasive in Los Angeles, which is to say, I think, that Homeboy has helped shift how people see, 'what if we were smart on crime rather than just tough?'

Lee Camp: In addition to that memory being harder to retrieve, are there other kind of things as you look back that are are surprises to you or that you have to kind of remind yourself of, that, 'oh yeah, this is the way things have unfolded for me.'

Greg: Well, you know, in the early days, because we had eight gangs that were at war with each other, so [00:07:00] my whole being in the evening was on my big black beach cruiser patrolling.

[Lee laughs]

So I would go to all, I'd visit all eight gangs before I went to bed sometimes. This was--

Lee Camp: Wow.

Greg: --you know, till after midnight.

Lee Camp: Huh.

Greg: You know, and, and it was a kind of a calming kind of thing, where they'd see me, and it, we'd talk and 'why don't you go inside,' and 'you don't live here, I'll come back with my car and I'll take you home.' Or--

Lee Camp: Hmm.

Greg: --'put that Uzi down, are you sure you wanna shoot that guy?' You know, that kind of thing.

So in the early days, I would do peace [00:08:00] treaties, truces, and ceasefires, and, and I always say, I don't regret that I did that and I would never do it again. You know, it was one of those things. In retrospect, you see that, though on paper... it's kind of the outsider view driving the inside of what we ought to be doing.

So you think, oh, this is what we should be doing, kind of Northern Ireland, Middle East, let's get the warring parties to sit down. Huge mistake, because it serves the cohesion of the gang, which is not a good thing, and it supplies oxygen to gang life, equally not a good thing. So, so I look back on that and I go, yeah, I mean, it was a natural thing.

Now people still do it all over the country, and they still think that gang violence is about conflict resolution, but there is no conflict in gang violence. There's violence, but it's not about anything. It's not a conflict. So you can't sit the [00:09:00] parties down, which is always a kind of a misconception that people have, you know?

Lee Camp: So the notion of it giving oxygen to gang mentality or gang identity, is simply that-- I, I understand you'd be saying that when you sit them at a table or invite them to a table as gang members, that's reifying that gang identity.

Greg: Absolutely. And at Homeboy we now say we, we don't work with gangs. We work with gang members.

Lee Camp: Interesting.

Greg: And we don't recruit or cajole or coax, and everybody knows where we are. We call it the, you know, the magic of the swinging doors. You know, you, you open that front door. Welcome. Welcome mat, ticker tape parade. They come in and, a homie said, there's an aroma.

Lee Camp: Hmm.

Greg: You know. You know, it's the whole talk about the Kingdom, it's about kinship and connection and people immediately tasting beloved belonging and then wanting that. [00:10:00] But we don't try to, uh, go out to anybody, because it's like rehab. You know, we don't exist for those who need help, it's only for those who want it. So it doesn't work if you don't freely walk in the door.

Having said that, they're all on a continuum of readiness.

Lee Camp: Mm.

Greg: You know, it's always like an AA meeting, you know, like who's there? Somebody who's 20 years sober, somebody who's 20 minutes sober, and somebody who's drunk, but he's there.

Lee Camp: Yeah.

Greg: And it's, it that kind of fluid continuum and spectrum is a thing that always happens.

Lee Camp: And, and do you think then that - you used the word 'addiction' and you've alluded to AA - so do you see attachment to gang identity as an attachment or as an addiction?

Greg: It kind of is. You know, in as much as, you know, the opposite of addiction is community. And so community will always trump gang life.

Lee Camp: Hmm.

Greg: Once they have a taste of it. But it's all part of the longing of [00:11:00] people. Everybody is born wanting the same thing.

Lee Camp: Yeah.

Greg: So, once they kind of discover that... But it, in recovery, it takes what it takes.

Lee Camp: Yeah.

Greg: And in gang recovery, it's the same thing. It can be the birth of a son, the death of a friend, a long stretch in prison. It takes what it takes, you know.

But no amount of me wanting that guy to have a life will ever be the same as that guy wanting to have one. So...

Lee Camp: Right.

Greg: You know, I always say, ours is a God who waits and who are we not to? So you wait for people. It's frustrating 'cause you would like to accelerate people's feeling cherished and nurtured and accelerate the healing.

But it's, it's the same as I, I don't know how else you can do it except to wait for people to show up and to be as attractive.

Lee Camp: You say in your most recent book that you were angrier when you were younger, that you shook your fist a lot. What precipitated a change in you in that [00:12:00] regard?

Greg: Well, you know, I think part of it was I was burying so many kids. And there was a kind of a, you know, a killing of Karen Toshima who was killed in Westwood, which is where UCLA is.

And it's, uh, kind of a 'shishi, fufu' neighborhood. You know, it's where you'd go to movies and nice dinner, that kind of thing. She was a, uh, graphic artist and was on a date and got caught in the crossfire, in gang crossfire, and she was killed. And then suddenly, you know, it was a $25,000 reward, all these detectives were dropped from lots of cases and assigned to this one, police presence was intensified, and the reward was offered for information that would lead to the arrest and conviction of whoever did this.

Now, at that juncture, that was kind of the climate, and at that moment I was burying eight kids in a three week period. And, and it was clear that one life [00:13:00] in Westwood was worth, you know, the 35 I had buried at that point.

And so, so you wanted their lives to matter, you know? But that was a different time for me. You know, I, I suspect I was-- you know, you get indignant when you're younger. And you don't wanna settle for moral outrage when you should hold out for moral compass, and they're not the same. And moral--

Lee Camp: Say, say that again. That's, that's so helpful.

Greg: You know, moral outrage is kind of where we get stuck, you know, where we shake our fist. And the hard truth of moral outrage is when I am outraging, it's about me. It's self-congratulatory. It strikes a high moral distance between me and others, and that's-- we settle for moral outrage. But we ought to hold out for moral compass.

So moral [00:14:00] outrage points things out. But moral compass points the way. You, you know, you wanna be able to point the way. You wanna say, "Over here! Let, let's imagine this." And then it, you insist on the undergirding principles that are so essential. We belong to each other, and every single human being is unshakably good.

And that's where I begin. Once you start there, you won't fall prey to the seduction that just has you shaking a fist, and basically not just denouncing something, but insisting that it be about me.[00:15:00]

It, it's subtle, I think.

Lee Camp: Subtle, but...wow. It was a terribly helpful distinction.

You pointed right there to one of the themes that recurs repeatedly in your public speeches and in your writing - that of kinship. Would you describe how that functions for you, in thinking about your work and in doing your work?

Greg: Yeah, I, you know, you don't go to the margins to make a difference. You go to the margins so that the folks at the margins make you different. And so then it ushers in this kind of exquisite mutuality.

I remember there was a woman... I was at a conference in Rome and we had this, kind of, social justice conference or something, and we were in small groups, and this woman, with great sadness, said that she had left work with refugees - really undeniably difficult work - [00:16:00] and she felt guilty about doing that. And then she said, "I think, you know, there were some moments of joy." And then she proceeded to talk about successes, you know, outcomes, measurable things. And I thought, oh, she's mistaking success for joy, and they're really quite different.

Lee Camp: Hmm.

Greg: And so the essential piece of kinship is to purify your narratives a little bit, you know?

Nobody has ever attended a graduation ceremony that didn't say, you know, go and make a difference.

Lee Camp: Yeah. [Laughs]

Greg: But make a difference is really about, if I'm there to make a difference, then it's about me. If I'm there to rescue, save, or fix, then it's about me. And the principle is, it can't be about you.

So in the gospel, when Jesus says it's really hard for rich people to enter the kingdom, it's not [00:17:00] about bank accounts, you know? It's about humility, and that the understanding of Jesus, of rich folks, is that there's not a lot of humility. It's really hubris. And so, can you receive people?

And, there was a homie I met in Houston who... doing hardcore gang intervention in the streets of Houston. And he said, "how do you reach them?" You know, he kind of pleaded with me after a talk, "how do you reach them?" Meaning, gang members. And, and I said, "well, for starters, stop trying to reach them."

[Lee laughs]

You know? Can you be reached by them?

Lee Camp: Huh.

Greg: Now, that's a whole other stance that's different. That's not, I'm gonna go make peace. I'm gonna enter into relational wholeness with people. That's hugely mutual.

Lee Camp: Hmm.

Greg: And I'm gonna only begin, and only do one thing, which is I'm gonna [00:18:00] allow my heart to be altered. I'm gonna be reached by this person. I'm going to receive. When I took this course from Henri Nouwen at Harvard Divinity, I remember a woman asked him, "what is ministry anyway?" And, and he was quite frustrated with the question.

He said, "can you receive people?" He said, "that's it." Can you receive people? Which again, feels so passive, if, were it not for the fact that it's the most liberating thing--

Lee Camp: Yeah.

Greg: --for somebody to be received.

Lee Camp: Yeah. And, well, and you say somewhere that you've decided that key to all this is simply the practice of showing up.

Greg: It feels like you're not making something happen.

Lee Camp: Yeah.

Greg: That you're not making a difference. Which is why people burn out, you know, because it's about them.

Lee Camp: Yeah.

Greg: And they're trying to fix and save. But if it's about the other, and if all you do is love being loving [00:19:00] and you receive people and you allow yourself to be reached and heart altered, then it's eternally replenishing. You will never burn out.

I mean, it's kind of the key. And I think that's an important thing, especially in ministry, as people wanna serve. You know, it's hard to enter into kinship with people if it's about you or if it's about hubris rather than humbly accepting people where they are.

Lee Camp: You're listening to No Small Endeavor, and our conversation with Father Greg Boyle.

I love hearing from you. Tell us what you're reading, who you're paying attention to, or send us feedback about today's episode. You can reach me at lee@nosmallendeavor.com.. You can also get show notes for this episode in your podcast app or wherever you listen.

These notes include links to resources [00:20:00] mentioned in the episode, as well as a link to a transcript.

Coming up, Father Greg Boyle tells some truly breathtaking stories on entering kinship and reteaching loveliness.

Greg: You know, it's hard to enter into kinship with people if it's about you or if it's about hubris, rather than humbly accepting people where they are.

Lee Camp: I love the story I've heard you tell about, I think you call him Mario, perhaps on a trip back to Gonzaga, which I think exhibits so well this kinship, an unexpected kinship. Would you be willing to [00:21:00] share that with us?

Greg: You know what's funny, stories, you know, you kind of retire them, you know, and you don't tell 'em for a long time. [Lee laughs]

But, but I remember he was quite panicked, uh, he and another guy, and we were gonna go to my alma mater where they had forced the incoming freshman class to read my book against their will. [Lee laughs] And so, you know, I've taken endless, endless homies with me on trips and they're all kind of panicky, you know. But I've never seen anybody like this.

We were at Burbank Airport, which is kind of small, and it's one of those tarmac airports. You don't--

Lee Camp: No breezeway.

Greg: There's no breezeway. You have to walk out onto the tarmac and climb the stairs to board. And he was like, hyperventilating and, and I almost had to go find a bag that he could breathe in and I remember I saw two flight attendants, female flight attendants, and they both had Starbucks coffees and they were schlepping up the steps. And Mario, with great desperation, "when are [00:22:00] we gonna board the plane?" And I pointed at the flight attendants - "as soon as they sober up the pilots, um, we'll be able to get on the plane."

And then I remember, I walked him around the, the airport and he - and this is saying something 'cause we get about 15,000 folks a year walk through our doors - he's the most tattooed individual who has ever worked there, which is saying a lot.

Lee Camp: Huh.

Greg: I mean he, his arms are all sleeved out to his fingertips, neck blackened with tattoos, entire face covered in tattoos.

So I'm walking him through the airport trying to calm him down, and I was just startled at how people would clutch their kids more closely and step away. And I thought, wow. Because to this day, he still works there. If you were to walk in and ask anybody, who's the kindest, most gentle soul here, they wouldn't say me. They would say, Mario.

And, uh, the [00:23:00] day won't ever come that I have more courage or I am closer to God than this guy. So we get to Gonzaga, and I remember they gave, they never-- they have the big talk, you know, on, on the evening of, Tuesday evening or something. But what they don't tell you is they have all these classrooms that you're supposed to visit throughout the course of the day. [Lee laughs]

So I said, "look, you know, I want you guys to get up and talk and-- 'cause I'm gonna speak tonight, you know," and, and they were absolutely panicked, but they did a good job, you know, and, the stories of terror and torture, and honest to God, if their stories had been flames, you'd have to keep your distance, otherwise you'd get scorched.

And I look back and I think I wouldn't have survived a single day of either of their childhoods, so, I don't think I did this that regularly, but I said, "Get up before me [00:24:00] and just give a little snapshot. So that I could, you know, include you in the question and answer period."

And it was like standing room only, packed, thousands of people sitting on the floor. I mean, total violation of fire code. And so they get up, and especially Mario was petrified and trembling, but they did a good job. And then I did my 45 minutes, then I invited them up and I said, "yeah, questions."

And a woman stands up, she-- "Ah, I got a question for Mario." You know, first question out the gate. So he's just a tall drink of water, skinny guy, gets up to the micron. "Yes?" And he's terrified. And she goes, "Well, you say you have a son and a daughter. They're about to enter their teenage years. What advice, you know, what wisdom do you impart to them? What advice do you give them?"

And Mario, uh, stands there getting a frigging hernia trying to come up with the right [00:25:00] answer. And I can tell he is starting to kind of crumble under the weight of it, then finally, he just ekes out, "I just," and then he stops. And then he kind of holds his face in his hands and people don't know if he can continue.

And then he says, "I just don't want my kids to turn out to be like me."

And there's silence, until the woman who asked the question stands, and, and says, with great tears, "Why wouldn't you want your kids to turn out to be like you? You are loving, you are kind, you are gentle, you are wise. I hope your kids turn out to be like you." And a thousand total perfect strangers stand and they won't stop clapping.[00:26:00]

And all Mario can do is hold his face in his hands, overwhelmed...that this room full of strangers had returned him to himself, and they were reached by him, which returned them to themselves, which is the way it's supposed to work.

Lee Camp: Thank you. It's beautiful. It's beautiful.

That phrase, you ended that story with, 'returning to ourselves,' that's another one that shows up often in your writing and your speaking. And I'm about to share a quote from the poet Galway Kinnell, but [00:27:00] I will say that especially in Tattoos uh, From The Heart-- On, On The Heart, um, I wanna go back and just collect the quotes you've got in there that hold these stories together.

There's so many beautiful-- and it's like...you got Merton, you've got Wendell Berry, Pema Chodron, Emily Dickinson, Mary Oliver, and so forth. Sh-- it shows your MA in English, I suppose. [Greg laughs] It's being put to good work there.

But you quote Galway Kinnell: "Sometimes it's necessary to reteach a thing its loveliness." And it seems that this is a particularly helpful way to construe what it means to be human, you know, to return to ourselves.

I love, and my students, I'm sure, get tired of hearing me talk about Irenaeus, second century, you know, "The glory of God is a human being fully alive."

Greg: That's right.

Lee Camp: And I hear that phrase you use, 'being returned to ourselves,' as sort of synonymous with that sort of vision of life.

Greg: Well I also think, you know, I mean, it's a wonderful poem.

It's a little [00:28:00] bit like-- people talk about second chances. And there was a homie who worked at the silk screen, who, actually he's the supervisor there, and he said, "Whoever gave them their first chance?"

Lee Camp: Mm-hmm.

Greg: And so it's, reteach somebody their loveliness as if it had been taught to them before. So that's kind of a misconception, because it often hasn't been. But when you talk about unshakable goodness, there are no exceptions to that. And part of our being stuck in moral outrage is we think there are plenty of exceptions to the, you know, unshakable goodness piece. So you have to kind of believe that every human being has that, the loveliness, that is their truth. And surely there are things that impede people from seeing that truth.

You know, it's about the human being, glory of God, fully alive, but it's also [00:29:00] the glory of God, you know, in holding the mirror up and reteaching loveliness.

Lee Camp: Mm-hmm.

Greg: And telling people that truth. Carl Rogers talks about 'prizing,' which isn't so much praising, you know, it's--

Lee Camp: Huh.

Greg: --It's about this notion of fully accepting a person, and then prizing who the person is, and that is about the most foreign land that anybody has traversed.

And, at Homeboy, you know, which is kind of a...it's the front porch of the house everybody wants to live in. It's the, it's a model, I guess, of a paradigm that could be different, where only in a community of beloved belonging, where everybody's engaged in repairing and attaching and repairing severed belonging - 'cause everybody, that's where they begin. They've had belongings severed. And it's never too late to repair that and to attach. We [00:30:00] have an 18 month training program. That's what they sign on for. And they get paid, and it's, they're supposed, you know, they'll work in a bakery and et cetera, but they're also equal parts working on themselves in group and therapy.

But the whole culture heals, the whole culture of the place. So if it's true that a traumatized person's going to, you know, likely to cause trauma, it's equally true that a cherished person will be able to find their way to the joy there is in cherishing themselves and others. So then they are reteaching loveliness to others and so it, and then it becomes, that's where the joy is.

But the 18 months, we, it was, how did we arrive at that? You know, when we said, well, a year is probably too short. Two years is too long. Okay, 18 months. But then we looked back, and then just by kind of a coincidence, that 18 months is the time it takes, they say, for an infant to [00:31:00] attach to the caregiver. And we went, that's it.

You know? We hadn't thought of that, but then it became, our reason was, yeah, this is about attachment repair.

Lee Camp: Huh.

Greg: Where people who, you know, all of them, you know, all of them are a 9 or 10 on the ACEs, on the adverse childhood--

Lee Camp: Yeah.

Greg: --experiences spectrum. You know, I'm a 0 on the ACEs and I grew up in the same city as these folks. But that's just, you know, if you want to talk about white privilege, that's just, you know, the lottery of my parents and zip code and education and siblings and-- But then you can stand in awe at what folks have to carry and, uh, what brought them to walk through the swing of the doors at, at Homeboy.

Lee Camp: Yeah.

In one of your chapters, I think it's entitled, "Disgrace," and you tell the story about a, I [00:32:00] think a, a young woman coming to see you, who's kind of undone one day, and she says, "I am a disgrace."

So you work a lot in that chapter with this notion of undoing shame. And as you look back and think about poignant instances of that, what are some examples of how that's happened, or people in whom that's happened, or what's that looked like for you to see the undoing of shame or the dismantling of shame so that a new healthy attachment can occur?

Greg: Well, Marcus Borg, the scripture scholar, says that the principle suffering of the poor throughout scripture and history is shame and disgrace. And, and I think that's quite right. And so, it's the thing. It's the pervasive sense, not so much that they've done wrong, but that they are essentially wrong, and that they can't shake that.

And so the only way to counteract that huge power in their life is to [00:33:00] offset it with, you know, seeing them as God does, which is easy. You're not pretending. I'm gonna pretend that there is a reason to prize this person. That, that part has always been easy, you know, and it doesn't feel like it might be, you know, tattooed, menacing looking folks.

But, like, during the pandemic, because I have leukemia, they set up this tent outside, in the early part of the pandemic, and it was, think more Lawrence of Arabia [Lee laughs] - it was just a huge white, with windows, it was quite spectacular. It had a rug and my desk and you know, and they kind of surprised me with it, 'cause they were just petrified of me actually being in the building, you know?

Lee Camp: Hmm.

Greg: So we have a security guy named Miguel, who's just the largest guy, you know, who has ever, uh, worked there, and you know, has a big shirt that says 'security' on the back. And [00:34:00] so he's, um, he's kind of traffic cop, so he's escorted people in, make sure they have their mask on, and, and then he shows them how to leave, you know, how to exit.

And so I'm watching him, and he's-- especially with the younger homies who came in to see me, you know, it's-- and the whole thing is kind of, 'the godfather will see you now,' [Lee laughs] you know, and so they brought, bring them to me and, and they're six feet apart, and all this kind of stuff. And, and so then he would direct the young guys out and I would hear him say, "Hey Papa, you can leave this way."

Now, 'papa' is something you would call your son. And it's very affectionate and it's a loaded word because it's just steeped with a very healthy, good father-son relationship. "Papa, if you could just go out that way," you know?

Lee Camp: Huh.

Greg: Very tender. And then, uh, homie comes in later on and he sits down and he says, "You know that guy back there?" and he [00:35:00] points at Miguel and he says, "Well, he's my worst enemy in the whole world. And right now, he just gave me advice that consoled me," which seemed like a incredible word to use. And then, you know, he left. But at the end of the day, I called Miguel in and I wanted to prize him, sort of, you know, and I wanted to say, "Hey, you know, I noticed how, you know, you would say 'papa' to the younger kids that was so tender and carinoso, you know, affectionate."

And then I mentioned that kid who was his enemy, and he knew who exactly who I was talking about, and, "he so valued your advice to him." Well, he just-- big, huge hulk of a guy sitting in front of my desk, holds his hands and his face and just sobs.[00:36:00]

He says, "I have found my purpose here." Now, this is a guy, when he was 12, you know, lived with a stepfather who just would torture and beat his mother. And he was sexually abused by three adult relatives. And one day he came home and he couldn't find his mom and she was tied up and, and gagged in a closet.

And his stepfather once had thrown her through a window, like you see in the movies. And so...he killed him.

He was, whatever he was, 14, and he went to what we called then Youth Authority, which is where they send very young, seriously offending kids. [00:37:00] And he was there till he was 25, and then they sent him to prison for an additional 10 years, and now he works for us. But he's found his purpose. And I've never had to carry what that kid carried, and... So it's reteach his loveliness, but loveliness was a foreign land for a kid like this. But now he loves being loving. And was he always unshakably good? Yes. Did he always know it? Rarely.[00:38:00]

Lee Camp: You're listening to No Small Endeavor and our episode with Greg Boyle.

We're gonna take a short break. Coming right up, more from Father Greg Boyle on gladness in the midst of tragedy.

Welcome back to No Small Endeavor - exploring what it means to live a good life. I'm Lee C. Camp.

If you're just joining us, today we're joined by Greg Boyle discussing his work in Los Angeles and beyond, as founder of the world's largest gang member rehabilitation program in the world, called Homeboy Industries.

Near the top of this episode, we heard Greg say that the main impetus [00:39:00] for the work in which he has found himself was this:

Greg: The fact that I was burying kids. So 1988 I buried my first, and on Saturday I buried my 249th. And then I, on Thursday upcoming, I'll bury my 250th.

Lee Camp: This week you'll be conducting your 250th funeral. And... I I hear what you're saying about, on the adverse childhood experiences, your friends that you're working with, a lot of them are 9 and 10, and yours was a 0. But I also look at your ministry and think about the trauma of doing 250 funerals like this, of [00:40:00] young men and women that you love.

And so I wonder how do you take care of your, your own self? How do you deal with the... that surely has to feel traumatic at times, in, uh, tending to yourself.

Greg: Yeah. You, you learn... as a homie who I buried, named Moreno, used to say, "death is a punk." He said that when his brother died in his arms, and the...the guys who shot him came back to see if he was also dead, and he had to pretend as he was lying there that he also was dead. And then two years later he was killed. But after his brother died, he said, "death is a punk." How was that different from, "death where as your sting?" Or, Paul says death had no power over him. It couldn't hold him, it says.

And [00:41:00] so it doesn't mean that you kind of don't feel things. But if you don't put death in its place, then you'll be toppled by it. You'll be toppled by life itself. And so, coupled with, you know, how do you stay anchored in the present moment, and how do you delight in the person in front of you, because that's all you have, and we're only saved in the present moment.

So that keeps at bay a certain thing. You don't get depleted, because you are delighting in the luminous now.

Now that may feel like you're not grieving, but you allow grief to not leave you where it found you.

Lee Camp: Hmm.

Greg: Grief sort of loosens you, and you allow that to happen. But most people kind of look at maybe what [00:42:00] I do for a living, and the presumption is ,that would be hard. And I've never had that experience. I really haven't.

It's mainly delighting - only because you choose, you choose to cherish with every breath you take. And you choose to delight in the person in front of you. That's hard to do because you have to decide today. And then you have to decide tomorrow. And it's never once and for all, but it's, you know, the practice doesn't make perfect, but it makes it permanent.

And so you are able to continue to do that without being depleted. And it's eternally replenishing because it's mainly people being tender with each other, and you laugh a lot. So the presumption is that death would win, [00:43:00] and it doesn't if you put it in its place, you know?

Lee Camp: The third main topic that I wanted to raise with you is, uh, the one again you just pointed to, and that is delight and gladness, which is another kind of thing that keeps repeatedly bubbling up in your writing.

You tell this story about being on a live radio show and something funny happening, and then you're driving away, and you said, "I steep in the utter fullness of not wanting to have anyone else's life but my own," which reminded me of one time hearing Stanley Hauerwas read a paper in which he opened up with a phrase from an Englishman who was a Oxford trained writer, [00:44:00] and then had decided to go back home and be a shepherd. And in one of his essays, this Oxford trained writer who's a shepherd is reflecting upon one day looking at the sheep and says, quote, "This is my life. I want no other."

I remember Stanley saying, this is what it means to live life, is to find yourself as you look back upon your life, being able to say, this is my life and this is what I'm grateful to receive and this is what I want.

But could you share with us more about what does it look like for you to learn to delight? And to learn to practice gladness?

Greg: Well, at homeboy there was a homegirl who was giving a tour. We always had, you know, three or four tours a day in big groups and from lots of countries and all over the place. And so the homies give tours, and they're walking through, [00:45:00] and I heard the homegirl say, "Here at Homeboy, we laugh from the stomach," [Lee laughs] which, everybody knows exactly what that is. That it's deep, it's profound, it alters you, it's not superficial.

And so again, during the pandemic, on his break, a guy named, we call him 'Chamuco.' And 'Chamuco' means - it's kind of a playful name that, in Spanish, for the devil. You know, it's kind of affectionate, actually, 'Chamuco,' because he has two big devil's horns tattooed on his forehead.

And he works in the-- to his credit, he's getting them removed. But he works in the bakery. So he, he comes in and he's, you know, dusted with flour and has his apron on and has his hairnet on and he has a mask on. So this is during the pandemic. And he's standing in front of my desk. And during the pandemic, I was able to fix his teeth. And he wanted to express his gratitude.

So he says, "Can I take off my mask to show you my [00:46:00] grill?" [Lee laughs] They always say grill when they're talking about-- "...to show you my grill." And so he, he's kind of broadly smiles, and big Colgate smile. And then he looks at me and he says, "Not only did you pay for this smile, you are the reason I'm smiling." And then there was this silence.

And he goes, "Hey, that's good. Write it down." [Lee laughs] And so I start to write it down and he's re, he's re-dictating it. "And not only did you pay..." And I think he was just hoping to get in my third book, and he did, he, right under the wire. I, I begin my epilogue with that. But the two of us, we just laughed from the stomach and uh, uh...

He went with me before the pandemic, with another guy, Robert, and we went to Sacramento to give some talks.

So we got in late, later than I like to on a Sunday night, you know? And so we're at Sacramento [00:47:00] airport, we're going to, uh, you know, the shuttle bus to take us to the rental cars. And so we get in, and I'm sitting across from this guy, Robert. Well, Chamuco goes and sits in the back, in the very back of the bus. And then, you know, people start to fill on the bus, but as soon as they see him, nobody wants to sit on either side of this guy.

So they assiduously do this fox trot to avoid him, until finally there are only two seats left on either side, and people very reluctantly sit down next to him. Then we start to go to the rental car thing. And if you've ever been there, it's a very kind of wooded, secluded, dark, and somewhere in the middle of this wooded and secluded place, the electric thing just, all the lights go off and the bus shuts down. And for some reason everybody is silent, and you can hear clicking, the "sorry, I'm working on it," and silent. And in this dark, secluded place, this voice [00:48:00] from the back of the bus says, "I saw this in a movie once. It does not end well." [Lee laughs] Well, the whole bus laughed from the stomach. And, and it was so joyous. And, and I, at that particular time, you know, you know, I'm almost certain that half the bus voted a certain way in a presidential election and the other half voted in another way.

But somehow, this kinship was brought to you by the guy with the devil's horn sitting at the back of the bus that nobody wanted to sit next to. And suddenly, kinship so quickly, and connection, and beloved belonging, brought to you by this guy.

Lee Camp: We've been talking to Father Gregory Boyle, founder [00:49:00] and director of Homeboy Industries in Los Angeles, California.

Thank you so much for your time and for your work and your goodness and delight in the world. Thank you.

Greg: Great to be with you. Thanks.

Lee Camp: You've been listening to No Small Endeavor, and our interview with Greg Boyle, Catholic Priest and founder of Homeboy Industries, the world's largest gang member rehabilitation program.

We gratefully acknowledge the support of Lilly Endowment Incorporated, a private philanthropic foundation supporting the causes of community development, education, and religion, and the support of the John Templeton Foundation, whose vision is to become a global catalyst for discoveries that contribute to human flourishing.

Our thanks to all the stellar team that makes this show [00:50:00] possible. Christie Bragg, Jakob Lewis, Sophie Byard, Tom Anderson, Kate Hays, Mary Eveleen Brown, Cariad Harmon, Ellis Osburn, and Tim Lauer.

Thanks for listening, and let's keep exploring what it means to live a good life together.

No Small Endeavor is a production of Tokens Media, LLC, and Great Feeling Studios.